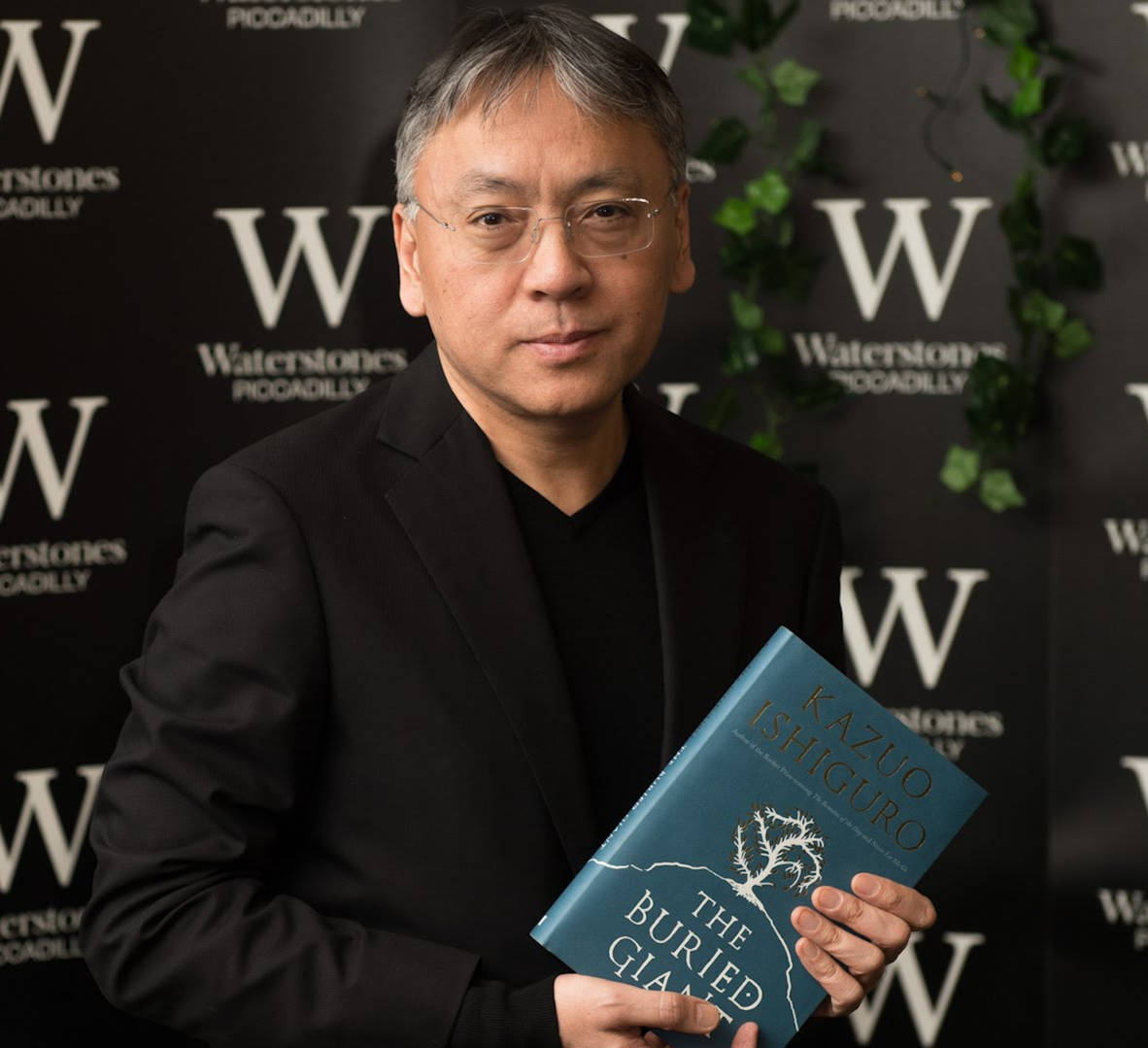

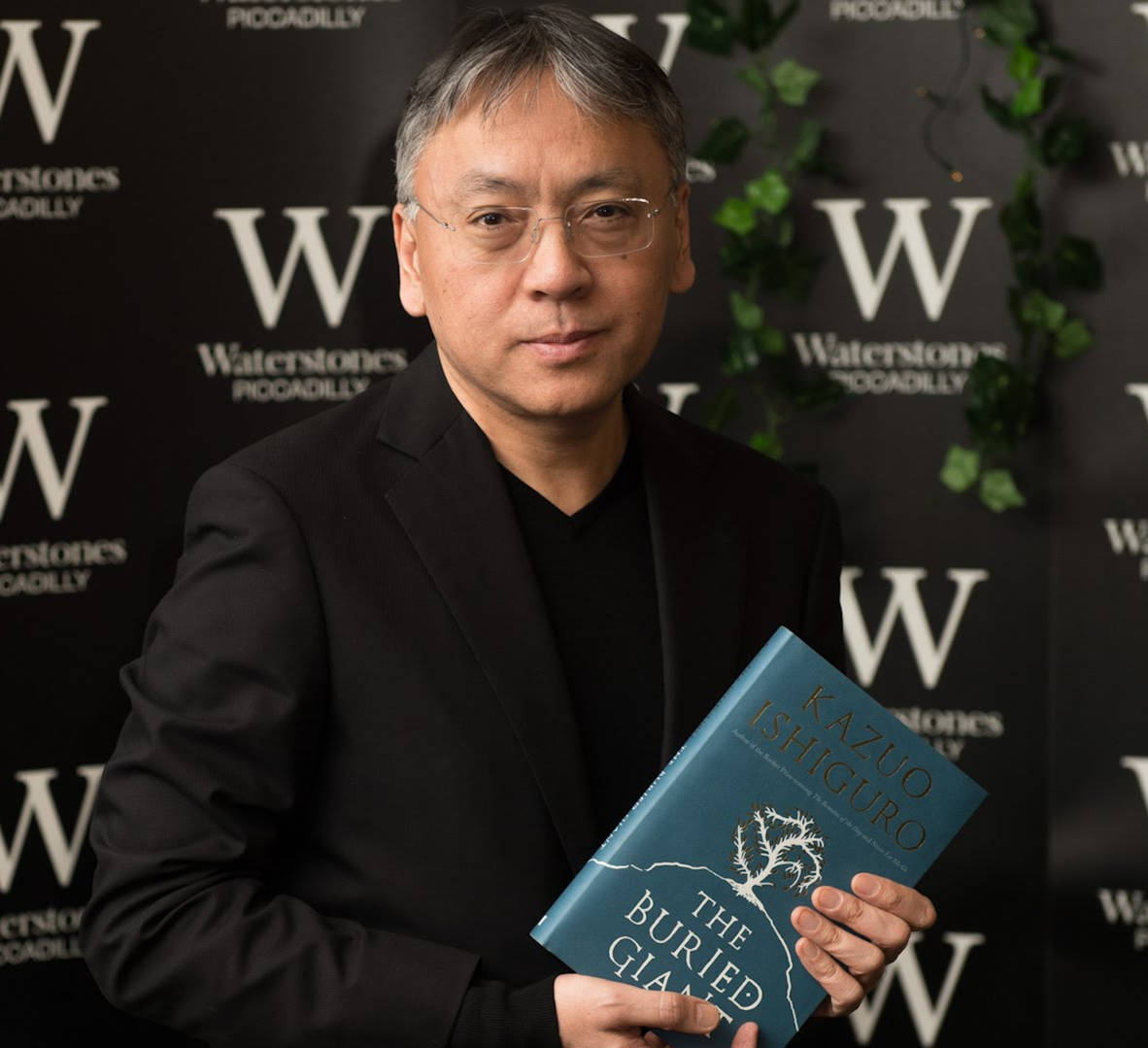

Different readers have had different experiences of The Buried Giant (2015), some finding it too crude an allegory, others enraged by its refusal to tell a straight story, still others engrossed and moved by its account of married love and the slow re-emergence of a half-forgotten atrocity. That, of course, is the point of the novel. It’s not a single story but a set of competing versions of the past, like Kurosawa’s great movie Rashomon (1950), and the great set pieces of the book are ones where all the characters talk at cross purposes, their readings of events utterly and often comically at odds with one another, their belief systems incompatible. Even individuals question their own version of events, thanks to the mist of selective amnesia that provides the novel with its plot and central metaphor: they are unable to be sure whether what they believe now is in any way related to their past commitments, and claim ignorance as to whether or not they have betrayed their comrades, allies, loved ones or ideals at some point in their former lives, however certain they claim to be of their faiths and loyalties here and now. They are not even altogether sure that they have forgotten things – a situation that caused particular anxiety to James Woods, the book’s reviewer for the New Yorker. Woods expressed consternation that their amnesia is itself unreliable, and that at times they seem able to recover with ease memories they claim to have lost for ever only moments previously. But to complain that this situation doesn’t make for what you generally assume to be a satisfactory story is, I think, to fail altogether to understand what Ishiguro is doing to the notions of ‘story’, ‘history’, ‘myth’ and ‘fantasy’ in this most disturbing and touching of narratives.

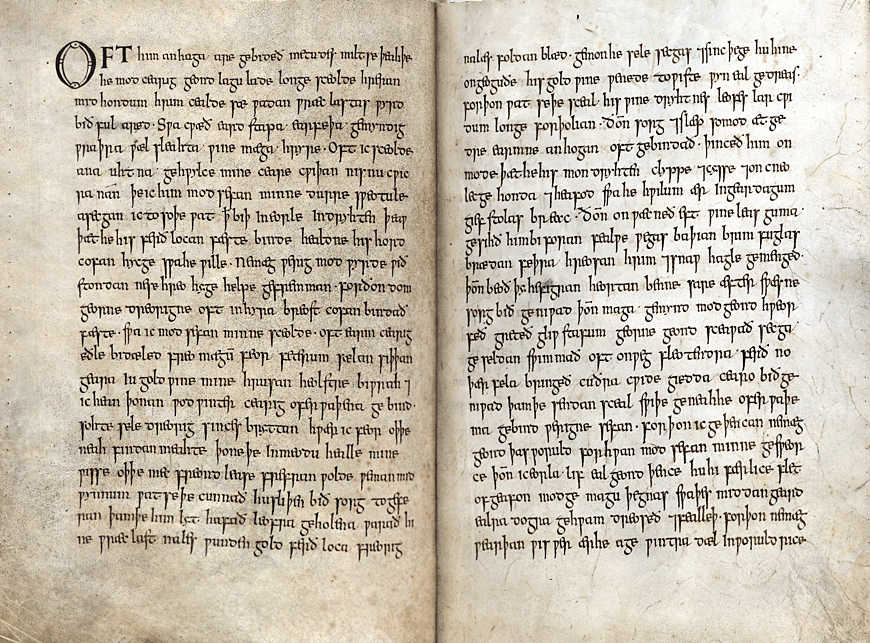

Everyone who’s read anything about the novel will know that it had a long and tortuous genesis. Ishiguro came up with the plot, he tells us, at an early stage, but took some time to settle in his mind whether to set it in Japan or Britain; it was a reading of that most ironic of Arthurian romances, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, that helped him make up his mind. He wrote a first draft which was dismissed by his wife as a failure because of its lavish prose style; he then wrote a second in a completely different register. The novel once completed, he was worried that his more serious-minded readers would dismiss it as ‘fantasy’. All these things work in its favour, to my mind. The book imports the traumatic experience of Japanese history – and the way this has been represented in art, especially film – into the Matter of Britain. Everyone knows about the multiple traumas and atrocities buried in Japan’s past, but the British have been more assiduous in burying theirs, from massacres in Ireland and India to the invention of concentration camps in the Boer War. This book invites us to exhume them, by revising that most cherished of British myths, the story of Arthur, who is supposed to have united a divided Britain by humane means – though even Malory ascribed to him an imperialist impulse that took him on the rampage through France and Italy to Rome. The novel ironizes romance and heroism as vigorously as Gawain or Beowulf. Its prose style is deeply strange. And its uneasy deployment of the tropes of fantasy invites its readers, whether or not they are well versed in them, to reconsider their function in literature and culture past and present. I think we’ll look back on it as a major achievement, and one that speaks to the many revisions of myth that have been going on in recent decades.

[I]ts uneasy deployment of the tropes of fantasy invites its readers... to reconsider their function in literature and culture past and present.

The book is as full of echoes as Shakespeare’s island in The Tempest. It begins in a grimmer version of a hobbit hole: a village of gloomy burrows, whose apparently genial communitarianism masks a propensity for bullying the weak which turns out to be a trait of just about everyone we meet in the story (the old couple we meet in the first pages have recently been robbed of their only candle, for no apparent reason, so that they have to live for the most part in the dark). A later incident, in which a Saxon warrior kills two ravaging ogres, recalls Beowulf’s killing of Grendel and his mother, while a visit to a monastery summons up the grotesquerie and ingenious misdirections of Umberto Eco’s Name of the Rose. The Greek ferryman of the dead, Charon, crops up repeatedly, and talks about taking passengers across to an island that sounds much like Avalon. One of the most fascinating figures in the book, from the point of view of his literary ancestry, is the knight Sir Gawain. His abnormal height, his advanced age and his thinness might make us think of Don Quixote drawn by Honoré Daumier, as does his apparent confusion over which remarks directed at him he should take offence at and which he should embrace as well-deserved compliments on his outmoded fidelity to a long-lost ideal. His clumsiness, his solitude, his white hair, his initial appearance in a wood of forgetfulness, his bouts of yearning after inaccessible young girls, might bring to mind the White Knight in Through the Looking Glass, who is also a figure of his creator Lewis Carroll. His fighting technique, like that of the Saxon warrior, is pure Samurai – a single well-aimed, deadly stroke is his preferred method of dispatching opponents (think of Kyuzo’s terrifying efficiency in Seven Samurai, or Zatoichi’s in Takeshi Kitano’s version). The mysterious widows who torment him with reminders of his past dark deeds recall the ghostly old women of Japanese tradition, such as the witch in Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood or the periodic apparitions in Satoshi Kon’s Millennium Actress. Beckett is present in much of the action, as is The Blair Witch Project, Hirokazu Koreeda’s After Life and Shakespeare’s King Lear. Echoes of films, books, poems (the name Beatrice summons up Dante’s Divine Comedy) tug at the reader’s memory at every turn, exacerbating the sense that past and future tragedies are always on the verge of re-emerging from obscurity as the story unfolds. And the overlapping of these different narratives and traditions reinforce too our sense that no story is singular – all are interwoven, and every reader will trace a different set of influences through the novel, all of them subverted by Ishiguro’s ironic tone.

When I say that characters in Ishiguro’s book – like his readers – read each incident differently, it should be stressed that this extends itself to the objects and creatures they see or which they signally fail to notice. Over and over again what they see differs: above all when it involves the supernatural or fantastic. The central characters, Axl and Beatrice, have poor eyesight, and often mistake things seen at a distance. For them the arm of an ogre, yanked off by the Saxon warrior Wistan, looks at first like an eyeless head, something like the Pale Man’s in Pan’s Labyrinth: ‘where the eyes, nose and mouth should have been there was only pimpled flesh, like that of a goose, with a few tufts of down-like hair on its cheeks’ (75-6). Only later does Axl realize that what he is looking at is not a head at all, ‘but a section of the shoulder and upper arm of some abnormally large, human-like creature’. Later, on an underground journey that recalls the visits of epic heroes to the Shades, Axl sees by candlelight the body of a dead bat where Beatrice sees the corpse of an abandoned baby. Axl entirely fails to spot the moment when Gawain slays the monster that lurks in this subterranean maze – he sees it run on after its death stroke but does not notice it has lost its head. Later still, Beatrice sees a distant row of soldiers in the mountains, which Axl takes for birds and the aged knight Sir Gawain for the tormenting widows who follow him everywhere. Looking down into a ditch, it takes Axl several minutes to distinguish the corpse of a goat from the body of the dying ogre that has been eating it: ‘Only then did he see that much of what initially he had taken to be of the dead goat belonged to a second creature entangled with it. That mound there was a shoulder; that a stiffened knee’ (288). Here again an ogre is presented to us as dismembered, but on this occasion its predicament elicits sympathy: Axl calls it ‘some poor ogre […] dying a slow death’ (289). Earlier, the boy Edwin saw three more seemingly dismembered ogres by a pond in a wood, one of them ‘crouching down on its knees and elbows at the water’s very edge, its head completely submerged’, so that ‘To a careless observer, [it] might have been a headless corpse’ (272). He too feels pity for them, as if his earlier abduction by ogres had given him an insight into their perspective, rendering them ‘human-like’ rather than monstrous. Meanwhile the warrior Wistan sees the partly submerged monsters by the pond as ancient trees, attributing Edwin’s view of them to a bout of delirium. Seeing things with distorted vision is, in fact, not just possible but highly likely in Ishiguro’s Britain – partly because of the physical condition of the land’s inhabitants. There are no corrective lenses for Axl’s eyes; Beatrice suffers from some nameless and possibly terminal affliction; Edwin has been wounded (though again, no one has a clear idea what by – a dragon, a cockatrice, an ogre?); Wistan is in a fever from wounds sustained in battle. As in Ishiguro’s previous novel, Never Let Me Go (2005), physical pain is a constant presence in the book’s landscape, serving to locate the appalling damage inflicted by tyranny and random violence in the inner organs of still-living victims. Everyone is journeying to a slow death, carrying mementoes of their mortality in their chests and bellies and sides, no matter how hard they seek to defend their minds from an awareness of its imminent approach.

The land partakes of the body’s sickness. The earth is full of slaughtered corpses, from the buried giant of the title to the remains of Saxon civilians slaughtered by Arthur’s knights in his final battle – no longer the heroic act of self sacrifice it was for Malory but a savage breach of promise, the deliberate violation of a carefully negotiated truce between enemies. Sir Gawain is reluctant to be buried anywhere but on top of a mountain for fear of the vengeful dead he might share the soil with. The Stygian tunnel through which Gawain, Edwin and the elderly couple travel is floored with bones. Christianity is less a religion than a means of distinguishing the Britons from the pagan Saxons; the Christians in the book have little confidence in God’s mercy, subjecting themselves to appalling torment as a means of anticipating the punishment he might mete out after their deaths, and only the pagan afterlife left behind by the departed Romans has any substance, manifesting itself in the ubiquitous figure of the ferryman. The land of chivalric romance is notoriously featureless, unlike the secondary worlds of epic fantasy, which are invariably given shape and substance by an accompanying map. Ishiguro’s Britain is closer to the former, with few names assigned to communities or features of the landscape – there’s a brief mention of Badon Hill at one point, but one cannot imagine a map being drawn of the land where it would feature. Place has come detached from place like the limbs of the ogre emerging from the mud in the ditch, entangled with the limbs of a goat.

Communities, too, have come apart in Ishiguro’s Britain. Families have been separated: Axl and Beatrice set out on their travels in a bid to find a son they may have driven off, or who may never have existed, and on their journey they encounter many more children who have been neglected, forgotten or betrayed. A little girl called Marta causes consternation in her village when she stays out after sunset; but before long the community gets distracted by something else, and by the time she gets safely home they have half forgotten she was ever missing. The boy Edwin seems at first to have a loving family, since his uncles muster the courage to attempt his rescue when he is abducted by ogres, but his relatives quickly turn on him when they think he has been infected by a vampiric bite from one of his abductors. Much later, Axl and Beatrice meet a young girl who has been abandoned by her parents, and who defends her younger brothers against another marauding ogre. The young generation have, in fact, become thoroughly at home in the cruel world they inhabit, and this acclimatization is part of what separates them from their elders. At one point the boy Edwin remembers meeting a teenage girl who has been tied up by her fellow travellers for their gratification. She is not particularly outraged by what has been done to her, and later when Edwin is in turn tied up and used as bait to attract the dragon he too takes it in his stride, expecting nothing better even from Wistan, the man he most admires. The little girl Marta is confident she will not get in trouble when she goes wandering, since she knows full well that her family will soon lose interest in looking for her, and like Edwin she can manage ogres: ‘I know how to hide from them,’ she tells Axl cheerfully (12). She shares, in fact, the attitude of Ishiguro’s narrator to monsters, as expressed in the opening pages: ‘One had to accept that every so often […] an ogre might carry off a child into the mist. The people of the day had to be philosophical about such outrages’ (3-4). Ogres are part of her community, like the humans who fear them, and both (as Edwin has learned long before we meet him in the narrative) can be equally deadly.

Each sacrifice – of oneself, of one’s enemies, of one’s children, parents or partner – triggers further bloodshed...

The most broken community in the novel is an isolated monastery in the mountains which occupies the site of a genocidal massacre. Religious communities are places of peace and contemplation, but Ishiguro goes to great pains (the phrase is apt) to show how they are also embedded in the landscape as well as the history of atrocity. His monastery is an elaborate physical and mental trap: Axl and Beatrice go there to get medical help for Beatrice’s ailment, but are betrayed by one of the monks into entering a monster’s lair, where he hopes they will be killed and eaten, and it’s implied that this happens regularly to the monks’ guests. The healer-monk whose advice they seek is himself dying from self-inflicted injuries sustained in penance for Arthur’s massacre of the Saxons. The monastery is an old Saxon fort which has been seized and turned to new uses by its British conquerors. The fort was designed not so much to protect the Saxons as to destroy the Britons in their moment of victory – like the young girl’s poisoned goat which kills the ogre even as the monster devours it. There are left-over booby traps in the repurposed fort, one of which is activated in an act of vengeance by the Saxon warrior Wistan; but the site itself seems to be destructive by virtue of its genocidal history, working on the consciences of its religious inhabitants until they subject themselves to Christ-like excruciations in a desperate bid to save their souls. In fact, as the novel goes on the imagery of sacrifice and betrayal proliferates in it, becoming in the end a pastiche of the Christian sacrifice to which the monks are ostensibly committed. Each sacrifice – of oneself, of one’s enemies, of one’s children, parents or partner – triggers further bloodshed, in a vicious cycle that predicts the continuing cycle of history from the so-called Dark Ages to the present.

My account of the book makes it sound unrelievedly grim, but it really isn’t, and this is largely thanks to the sometimes comic detachment of its style – a detachment that reinforces the sense that its characters can endure the monstrousness of their Dark Age situation precisely because of their wilful removal of themselves from the stark realities of past and present. Axl and Beatrice, Wistan, Gawain and the boy Edwin converse in an awkward succession of stilted politenesses, even when they are drastically at odds with one another; Axl calls his wife ‘princess’, and treats her like one, constantly striving to protect her from the pain and exhaustion their journey brings her, acquiescing to all her proposals even when they distress or hurt him. Wistan expresses unwavering hatred for the Britons who massacred his people and seeks to bequeath this hatred to young Edwin, his fellow Saxon; but he treats the Britons Axl and Beatrice with affection and respect, and behaves with ridiculous courtesy to Gawain even at the point when they’re about to spill each other’s guts. Edwin promises to hate all Britons when Wistan asks him to, but he clearly can’t see the point in it; the elderly British couple are his friends and so must be exempted from the blanket injunction, and if them, how many others? People, like ogres, can be liked and pitied even by those who seek their deaths – the young girl who poisons the ogre with her goat is afterwards sorry for what she has done and claims she didn’t intend it. Even the dragon is a pitiable creature, worn out by its hard life like Axl, Beatrice and Gawain; it must be killed, but it is also a victim, forced into spreading oblivion across the land by Merlin’s spells, and its would-be killers feel no resentment as they approach its ailing body to lop off its head. The elaborate verbal courtesy, then, that people extend to one another in Ishiguro’s Britain is not just a means to cover up their true feelings (whatever these may be – the novel suggests that human feelings are always conflicted). It also serves to manifest their genuine affection for one another despite all the cultural and historical pressures that combine to drive them apart. Courtesy endures even after the stark realities of the past have been unveiled thanks to the dragon’s death, and it’s this courtesy, like the unfailing courtesy of Gawain in the Green Knight, that one remembers afterwards, rendered all the more poignant by the savage setting in which it somehow survives.

The chief characteristic of the book’s style – especially the dialogue – is that it reads like a work in translation. It is clear and spare, stripped of rhetorical flourish and colloquial punchiness, and stripped too of dialectal elements specific to a certain class or locale or historical period – in marked contrast to the language of, say, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, or the Wakefield cycle, or Morris, or Tolkien. I was reminded as I read of the translations of Homer and Ovid I read as a child in the continuous prose of the Penguin Classics series, largely composed by its founder, the poet and scholar E V Rieu: a prose which reminded you at every moment that what you were encountering was at several removes from the original, yet which also miraculously seemed to convey certain crucial elements of that original in heroic defiance of the mists of time. Here is Ishiguro’s version of Rieu, in a passage from near the beginning where the elderly couple are striving to remember their departed son:

‘Some days I remember him clear enough,’ she said. ‘Then the next day it’s as if a veil’s fallen over his memory. But our son’s a fine and good man, I know that for sure.’

‘Why is he not with us here now, princess?’

‘I don’t know, Axel. It could be he quarreled with the elders and had to leave. I’ve asked around and there’s no one here remembers him. But he wouldn’t have done anything to bring shame on himself, I know for sure. Can you remember nothing of it yourself, Axl?’

‘When I was outside just now, doing my best to remember all I could in the stillness, many things came back to me. But I can’t remember our son, neither his face nor his voice, though sometimes I think I can see him when he was a small boy, and I’m leading him by the hand beside the riverbank, or when he was weeping one time and I was reaching out to comfort him. But what he looks like today, where he’s living, if he has a son of his own, I don’t remember at all. I was hoping you’d remember more, princess.’

‘He’s our son,’ Beatrice said. ‘So I can feel things about him, even when I don’t remember clearly. And I know he longs for us to leave this place and be living with him under his protection.’ (28-9)

The language here is formal, for all its occasional gestures towards the demotic (the contraction of ‘has’ in ‘as if a veil’s fallen across his memory’ is a classic bit of rather stiff translator’s colloquialism). There is no attempt at a lyrical rhythm. The vocabulary is simple and clear, as if selected by an adherent of the Campaign for Plain English – or deployed in a classroom by a teacher keen to ensure her charges can readily follow her words. Beatrice speaks of her son in platitudes: ‘our son’s a fine and good man, I know that for sure’, she tells Axl, awkwardly but confidently combining a claim to certainty (‘for sure’) with the vaguest of epithets (‘a fine and good man’), and she does the same twice more in this short passage: ‘he wouldn’t have done anything to bring shame on himself, I know for sure’; ‘He’s our son […] so I can feel things about him […] And I know he longs for us to leave this place’. Axl, meanwhile, remembers only gestures, detached from the markers of individuality, face and voice – the ‘things’ Beatrice repeatedly refers to. Both of them, then, represent their son in what are effectively verbal fragments, like the fragments of the ogre in the ditch. The most translation-like feature of the passage, perhaps, is its frequent use of the present continuous – a tense not so very often used in colloquial English: ‘sometimes […] I’m leading him by the hand […] or when he was weeping one time and I was reaching out to comfort him […] he longs for us to […] be living with him under his protection’. The overall effect is to suggest that Axl and Beatrice are constructing their son not from memories or instincts – however tenuous – but from what their culture generally assumes a good parent would think about his or her offspring: that he is ‘fine and good’, that he would never misbehave, that he wants them to be with him as a good son should. The continuous present indicates that their thoughts about him are not bound by time, as memories are, but permanent features of their mental landscape. Their courteous attitude to one another’s perspective (‘Can you remember nothing of it yourself, Axl?’ […] ‘I was hoping you’d remember more, princess’), suggests that they are keener to achieve consensus than to draw attention to some striking recollection of their own that might clash with their spouse’s. Axl and Beatrice are dedicated to holding things together, and the strange translator’s English they speak, treading a tightrope walker’s path between abysses of contention and contradiction, is their sole defence against the imminent collapse of all agreements among the inhabitants of the damaged Britain they wander.

At various points in the book the consensual translator’s language shows clear signs of the intense strain to which it’s being subjected by the old enmities, buried atrocities and conflicting emotions and loyalties it conceals. Sir Gawain, in particular, sometimes lapses into incoherence as he seeks to sustain his image as the solitary warrior dedicated to preserving his idealized monarch’s vision of universal peace at the cost of personal relationships:

I had a duty. Ha! And do I fear him now? Never, sir, never. I accuse you of nothing. That great law you brokered torn down in blood! Yet it held well for a time. Torn down in blood! Who blames us for it now? Do I fear youth? Is it youth alone can defeat an opponent? Let him come, let him come. Remember it, sir! (309)

The collapse of distinctions here – it’s hard to tell which ‘him’ or ‘you’ or ‘us’ is referred to in successive sentences – has the effect of conflating all the characters in the book, making them all equally the guilty parties and the victims of the cycle of violence in which they are caught. In this it replicates the way implements make their way from one person’s hands to another in Ishiguro’s novel. One hoe in particular – a farming tool consisting of a long pole with a downturned blade at one end – is at one point to be found in the hands of a young girl, who uses it to exact an appalling vengeance on the man who raped or murdered her mother and sisters (241): a vengeance so terrible that it shocks Sir Gawain and violates his sense of the girl as an innocent victim. Later in the book an identical hoe is seized by Axl as he fights to defend Beatrice against a swarm of pixies, tiny malevolent beings whose disturbing resemblance to young children serves utterly to compromise Axl’s apparent act of chivalry (263). The hoe, like the plain language used by Ishiguro’s characters, is no more than a tool, but the second time we encounter it this instrument has been contaminated by the previous encounter – hoes have become instruments of appalling sadism, and this association is impossible to shake off as Axl attacks the swarm of creatures whose ‘collective voices seemed to him to resemble the sound of children playing in the distance’ (263). At this point Axl, like the girl, is no longer identifiable as simply criminal or victim, aggressor or defender against aggression. The language of Gawain’s speech extends this moral confusion to everyone else in the novel – Wistan, Axl, Gawain, Edwin, the long-dead Arthur, and the young people (like the hoe-wielding girl) who can so readily accommodate themselves to the violent world King Arthur bequeathed to them. All have been cross-infected by association with atrocities, just as the boy Edwin was deemed to have been rendered ogreish by the bite he sustained from an ogre. I, you, we, he, she, they – all pronouns are in a similar position, interchangeable in any given sentence relating to guilt, shame, pain or sudden aggression.

[H]e leaves his sympathetic readers with little doubt of...the capacity of fantasy to represent the pain involved both in sustaining and dissipating the mists of illusion.

The one exception may be Axl’s wife Beatrice – though even she is to some extent compromised in Axl’s mind by one highly unreliable memory that surfaces towards the end of the narrative. Beatrice’s mission throughout is to recover the memories obscured by the mist, first by visiting her lost son and later by helping slay the dragon who gave rise to the mist of forgetfulness. Her conviction that Axl and she have nothing to fear from the return of memory is always touching, but the trajectory of the story tends to expose it as a comforting dream or fantasy, sprung from the fund of comforting fantasies by which people preserve their sense of order, love and justice. I suspect this is one of the reasons Ishiguro turned to fantasy in this novel: as a means of exploring the quotidian fantasies we cling to – chief of all, perhaps, the fantasy that we live in a civilized epoch, firmly founded on previous epochs of civilization – which are aided and abetted by the patterns of our everyday discourse.

The final chapter draws out this theme with consummate skill. Throughout the novel points of view have shifted from time to time – we see things successively from Axl’s, Edwin’s and Sir Gawain’s perspectives – but this is the first time we have been invited to see an episode from the perspective of a fourth individual – one of the Charon-like boatmen who have cropped up periodically since soon after the beginning of the narrative. It’s also the first time we have been given a first person narrator – apart from the anonymous first person narrator of the first chapter (are we meant to believe, then, that this is the boatman, that we are being addressed throughout the book by the ferryman of the dead?). In the last chapter, the elderly couple finally seem to be approaching the moment of their journey that Beatrice, in particular, has anticipated from the beginning, when they will be reunited with their long lost son. Beatrice is convinced the happy ending will soon take place and that the three of them will be permitted to cross to the island where her son lives and inhabit it for ever in blissful unity. The boatman’s perspective, however, gives us access to his intentions, which increasingly suggest that her hopes are misguided. His narrative is filled with expressions of pity for the couple, as if he is convinced they will soon be permanently parted – and that there’s nothing he can do about it, in spite of his agency in parting them. ‘I cannot lie and I have my duty’, he says at one point (348) as he directs them to the shack where their passage to the island on his boat will be arranged (in this book the island is a topographical emblem of isolation, as in Donne’s celebrate sermon – though Beatrice sees it as a site of recovery like the Avalon of Arthurian legend). The word ‘duty’ used here by the boatman has by this time been contaminated by Sir Gawain’s repeated use of it to denote the dubious responsibilities he was assigned by Ishiguro’s demythologized Arthur.

Axl, meanwhile, becomes increasingly – and as the reader know, rightly – suspicious of the boatman’s intentions, but continues to sustain Beatrice in her fantasy of a joyful conclusion to their adventures. Beatrice speaks of the boatman’s kindness with conviction, as she did of her son in the earlier passage: ‘He’s a good man and won’t let us down’ (360). Axl does not believe it – he has caught the boatman in one lie at least and is certain all his other promises too are lies; yet he chooses not to puncture his exhausted wife’s last dream; and to the last moment they spend together he sustains her fantasy, although he does not share it. The book ends with the old woman happy in her conviction that her future will be a loving one, and the old man wandering away from her, lonely in the dark.

The reader is left wondering which condition is better: Beatrice’s knowledge, which is really ignorance, or Axl’s, which the reader knows to be well founded. The question is not an easy one to answer. Beatrice leaves with the boatman, certain she will be reunited with Axl and her on on the other side. Axl leaves alone, certain that he has given his wife – at least for a time – the happy ending she longed for, in the only way available to him. His own unhappiness is assured – but so too is her happiness, however long it lasts. Axl asks a similar question of Beatrice not long before they part: ‘Could it be our love would never have grown so strong down the years had the mist not robbed us the way it did? Perhaps it allowed old wounds to heal’ (361). In the end he believes, as he has done since the beginning, that it is best to leave the mist of illusion in place – ironically enough, since it was the ignorant Beatrice who always insisted that it is better to remember every detail of a relationship than to lose even a single memory to time, however painful. Ishiguro leaves us to judge for ourselves which of these two perspectives we share. One thing, however, he leaves his sympathetic readers with little doubt of: the capacity of fantasy to represent the pain involved both in sustaining and dissipating the mists of illusion.

He also leaves us with a memory: that of the only true act of self-sacrifice in the novel. I said earlier that every sacrifice in the book triggers further bloodshed. From what we can see, this is not true of Axl’s – though it’s also not clear how far he had a choice in making his sacrifice, since the sense of its having been somehow predestined has been implanted in the reader by our earlier encounters with the boatman. Then again, the one event in all our lives which is predestined is the fact of death, and the parting with loved ones this entails – a parting considered in many religions to extend into the afterlife, where there will be no marriage or giving in marriage, as the Bible tells us. Axl’s parting from his wife, then, is both the most painful moment in the book and the most movingly memorable.

For me this makes it a moment of light in Ishiguro’s meditation on Dark Age darkness; though it’s a fading light, like the ‘low sun on the cove’ to which Axl moves in the final sentence. We should be grateful for it.

You can find more of Rob's eloquent reviews, as well as short stories and other delights, at the City of Lost Books.

]]>

. These verbal (and textual) duels typically comprised insults focussing on a foe’s sexual perversion, their lack of courage in battle, or their physical ineptitude, and were frequently, joyously vulgar. Think Christmas dinner conversation with your favourite drunk aunt.

. These verbal (and textual) duels typically comprised insults focussing on a foe’s sexual perversion, their lack of courage in battle, or their physical ineptitude, and were frequently, joyously vulgar. Think Christmas dinner conversation with your favourite drunk aunt.

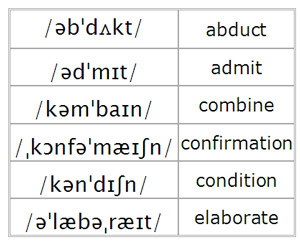

Example of phonemic transcription (Source: http://www.azlifa.com/pp-lecture-8/)

Example of phonemic transcription (Source: http://www.azlifa.com/pp-lecture-8/) Institut de France, home of the Academie Francaise

Institut de France, home of the Academie Francaise