Rainbow Rowell, Carry On: The Rise and Fall of Simon Snow

Heavy spoiler alert! If you haven’t read Carry On, desperately want to, and read this review first, you really only have yourself to blame for what happens next.

The highest compliment I can pay Carry On, my George Cross or Légion d'honneur, is that my childhood (a somewhat more distant realm than I’m currently prepared to recognise) would have been immeasurably improved by its presence. Fantastically well-written and edited, Rowell’s prose is hypnotising – such that it renders a dissolution of borders between the reader and the world she offers, an amorphous state interrupted only by the end of a chapter or being twatted by one’s hungry cat.

Of course, the premier pleasure of this novel is the burgeoning romance between the eponymous character and his arch-nemesis, Tyrannus ‘Baz’ Basilton Grimm-Pitch: paced with exquisite insufficiency, each encounter (or collision) between them nuanced and wonderfully imprecise, it is, without doubt, one of the most enjoyable and – crucially – satisfying same-sex relationships in literature I’ve encountered.

Of course, I could fanboy with abandon for the rest of this review but, alas, time isn’t as charitable as it used to be: places to avoid, colleagues to undermine, you understand. Instead, I’d like to draw your attention to two points that most captured my attention. Firstly, Rowell’s magic-system: it’s unlike any other I’ve encountered in fantasy literature (although I’m sure comparable systems exist and no doubt you’ll haughtily helpfully remind me of that fact via email or twitter).

I’ll be frank: Rowell’s magic-system gies me the thirst. A philologist’s wet-dream, it’s developed around the principles of language change and evolution:

“Magic words are tricky,” Snow informs us,

“Sometimes to reveal something hidden, you have to use the language of the time it was stashed away. And sometimes an old phrase stops working when the rest of the world is sick of saying it.”

Rowell’s magic-system: it’s unlike any other I’ve encountered in fantasy literature.

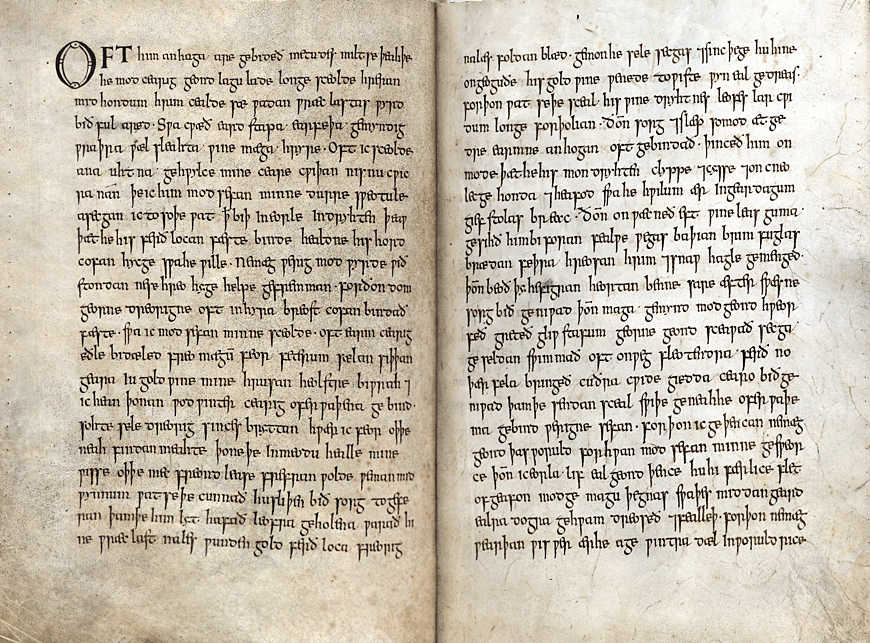

Isn’t that fascinating? I suppose we might think of a word like goldwine – often translated as the Old English term for Lord – it means ‘gold friend’: a kenning, or compound expression, that was deployed specifically to reference a generous leader. For example, in the poem Beowulf, the eponymous hero is referred to as goldwine G__ēata – the gold friend of the Geats; and Hrothgar, king of the Danes, is described as goldwine gumena – gold friend of warriors.

In the Anglo-Saxon poem, The Wanderer, the narrator ruminates on his past happiness in service, feasting with his comrades and enjoying the generosity of his lord, all now dead:

siÞÞan geara iu / goldwine minne / hrusan heolstre biwrah

Since long years ago / I hid my lord / in the darkness of the earth.

Spells, like language itself, lose efficacy with popular decline but regain a measure of value when historically contextualised (perhaps the modern incarnation of goldwine, having been processed through some considerable semantic shift, might be toryprick?). “The best new spells are practical and enduring,” explains Penelope, Snow’s formidable BFF:

“Catchphrases are usually crap; mundane people get tired of saying them, then move on. (Spells go bad that way, expire just as we get the hang of them.) Songs are dicey for the same reason.”

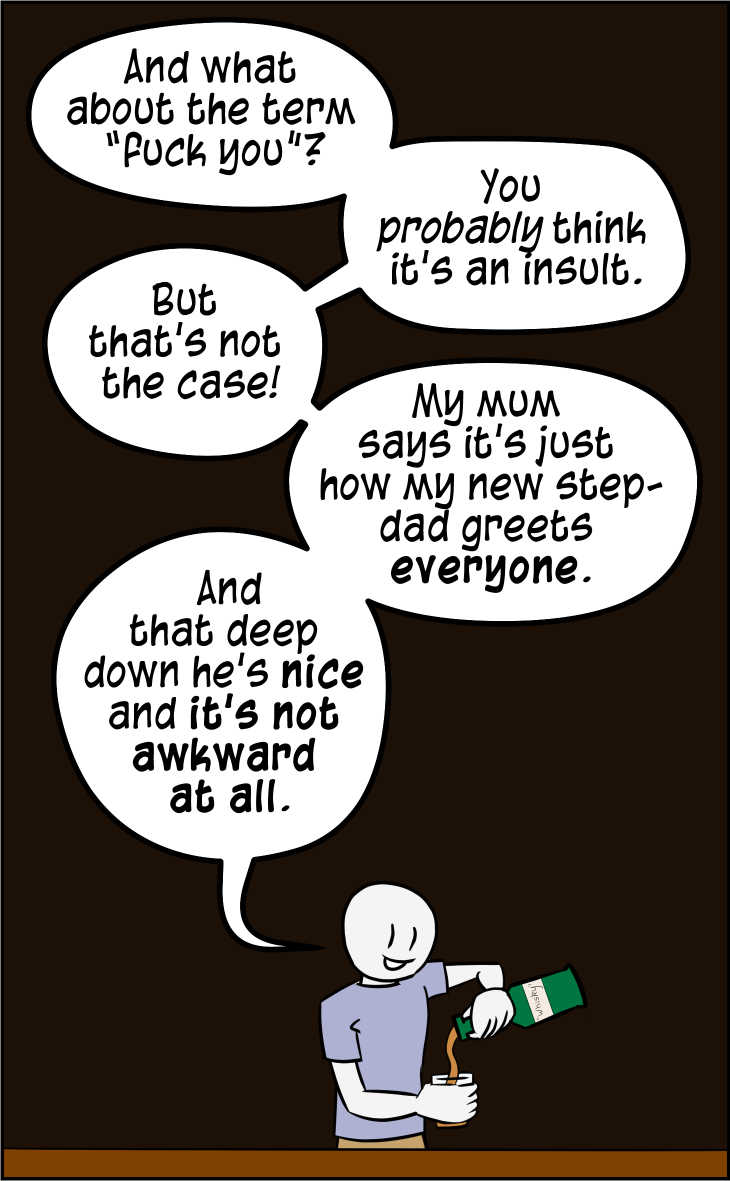

What makes the magic-system in Carry On especially charming is the arresting tension between descriptivist and prescriptivist thought extant along the demarcations of institutional attitudes and broader society. On the one hand, as Penelope mentions, spells develop, change and die with use (or lack thereof) – we might consider, as an illustration of this process, the word nice. A French loanword into Middle English (around the 14th Century), it has throughout its history meant (sometimes concurrently): foolish, stupid, ignorant, lascivious, wicked, extravagantly dressed, scrupulous or punctilious (in terms of reputation or conduct), fastidious or fussy, careful, strict, refined or cultured, discerning in terms of literary taste, virtuous, conversationally appropriate, timorous or cowardly, lazy or slothful, pampered or luxurious, strange or rare, shy or coy (affectedly so), requiring close consideration, subtle or exact, slender or thin, trivial, meticulous, tastefully discriminating, dextrous, doubtful, requiring careful handling, restorative, satisfactory, pleasant-natured. See the OED entry for the full extent of the wild ride that is nice.

Now, of course, it seems to be undergoing pejoration – one tends to use it ironically. If we describe something as ‘nice’, it’s code for ‘tolerably shit’. For example:

Me: Oh hey, Barbara – Timmy’s such a nice kid. I’d be happy to look after him more often.

Me to self: Infant mortality, don’t fail me now.

On the other hand, Simon describes ‘elocution’ lessons students undergo to correctly execute spells:

“Words are very powerful,” Miss Possibelf said during our first Magic Words lesson. No one else was paying attention; she wasn’t saying anything they didn’t already know. But I was trying to commit it all to memory. “And they become more powerful,” she went on, “the more that they’re said, and read, and written, in specific, consistent combinations.”

Spells, like language itself, lose efficacy with popular decline but regain a measure of value when historically contextualised.

“…speaking out, hitting consonants, projection” – even amidst the acknowledgement of linguistic change and development, there’s a need to fix, to attach ‘correctness’. Rowell’s magical system is a superbly-apt, and self-aware, paradigm for the struggles between prescriptivist and descriptivist attitudes to language, between conservative and transformation, stasis and flux. There seemed to be the inkling of a comparable approach emerging in The Philosopher’s Stone (recall the “It’s levi-o-saa” incident between Hermione and Ron) but that somewhat degenerated into a system of ‘this sounds Latiney enough, right? Cool. Boom. Magic’, ignoring the issue of prescriptivism altogether.

The second point that struck me in the novel was Rowell's handling of the ‘Chosen One’ trope. Carry On is often regarded as an ode to fanfiction, being as it is something of a Harry Potter pastiche. This wasn’t the case for me: I read Carry On as a response to the failings of Harry Potter (cue a thousand screaming Potterites jamming the postal system with envelopes of dog-shit destined for my door).[1] For example, the inescapable fact that Harry Potter was based in an exclusively heteronormative universe. “But Dumbledore was gay!”, I hear you whine. No – if it wasn’t clear in the books, it’s not the case. I’m intractable on this point.

Rowell creates a world where not only can gay people do magic (which should be obvious to everyone – Scottish gays historically rode unicorns into battle), they can even be the protagonists.

Even if we were to accept the tiny homo-crumb Rowling flicks to us (after her books are published), Rowell creates a world where not only can gay people do magic (which should be obvious to everyone – Scottish gays historically rode unicorns into battle), they can even be the protagonists. As such, Rowell takes Rowling’s tried-and-tested ‘Chosen One’ narrative wherein the hero of the story is predestined for great things (by, you guessed it, a prophecy!) and subverts it beautifully. Simon is bio-magically conceived for the sole purpose of fulfilling a prophecy that, as it turns out, was misread, resulting in a hero attempting to fulfil an ill-fitting destiny as best he can. All the while, the true subject of the prophecy, Ebb, happily tends her goats throughout, having opted-out of the system despite her supreme gift for magic. So subversive is Rowell’s treatment of, and so conditioned am I by, the established framework for the ‘Chosen One’ trope, I found myself suffering incredible frustration during my first reading. Only several completions later have I accepted the fact that Ebb isn’t going to be the magical saviour of Britain – it’s been a journey of personal development and awkward afternoon erections.

Carry On is undoubtedly one of the best pieces of fiction I’ve encountered – if, like me, you’re of a certain age where you’re not old enough to recall a youth before mainstream m/m romances but not young enough to only know a youth where mainstream m/m romances exist (though still in unsatisfying numbers), Carry On feels especially important, a poignant notice of how much sweeter things could have been. Aside from Rowell’s innovative exploration of language and magic, it’s a book that features protagonists who are gay and acknowledges the attendant issues they have to face but doesn’t confine its narrative scope to those issues. It’s a book that’s technically proficient, often hilarious and always intelligent. I’m indifferent as to whether you enjoyed it but it’s important that you know it made me very happy indeed.

Footnotes

[1] Editor's note: Given that I rather like Harry Potter, and tend to check the mail, please do refrain!

Further Reading

For more on the prescriptivist/descriptivist dichotomy, see:

- Prescriptivism v Descriptivism: A Very English Affair

- Part 2 of our interview with Catherine Sangster, from Oxford Dictionaries.

And, for his take on the Chosen One and Prophecy tropes, see our interview with Adrian Tchaikovsky.

No comments

Start the conversation…