Taken as a Genre

As someone born in the late 80s, I came of age with the new millennium. This meant, for me and many others, having just enough familiarity with the world of the 90s to recognize the utter madness of the post-9/11 period. Even from outside the United States I could see optimism giving way to a mix of terror and bloodlust. The 90s new economy was supposed to promise a world where war was an anachronism (though the peace always had its discontents). Instead, political and popular culture became a constant torrent of demands for violence. “We” were at war now, and the “homeland” needed to be defended. The bloodlust of the first day – my main memory of September 11 2001 itself is a man leaning out his car to be interviewed on TV demanding a nuclear strike against a “them” he can’t identify as anything more than Middle Eastern – escalated into two wars and a wartime fervour that didn’t abate for almost a decade.

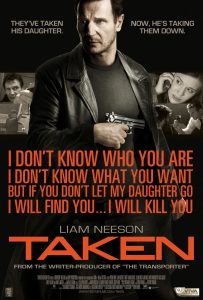

No film captures this cacophonous, almost desperate violence quite like Pierre Morel’s Taken (2008). A film that turned Liam Neeson from a serious dramatic actor into America’s favourite murder-dad. What I want to do here is look at one of Taken’s legacies. Specifically, I want to argue that Taken can be understood as a genre unto itself.

What does this mean, to say Taken is a genre? For starters, genres are ways we categorize works of art. Genres can be broad, like comedy or sci-fi. They can be more specific, like a ‘casino crime caper’ or ‘dystopian teenage romance’. In each case, what makes genres ‘genres’ is that these categories guide both creation and interpretation.[1] So a movie being a comedy means both that the people making it were using the idea of “comedy” to guide their decisions, and the people watching it were using the idea of “comedy” to appreciate it. To say Taken is a genre, then, means that there are movies which can be understood as “Takens”. To appreciate these movies, it’s not enough to understand that they share features with Taken, but to view them as “a Taken.”

Later I’ll go over three particular Takens but first we need to set up just what a Taken is. If it’s a genre, what are its distinctive features? What does it take to be a Taken?

Taken

Let’s start with the plot, which is most famous for revolving around Liam Neeson as murder-dad Bryan Mills. Mills starts the movie as an ex Green Beret and CIA officer who has been reduced to working security because nobody needs him anymore; his wife has left him for another man and his daughter thinks he’s a loser. On a trip to Paris, his daughter and her friend are kidnapped by vaguely-ethnic Albanian gangsters who plan to sell them into slavery. Mills delivers his famous monologue over the phone – “I will find you, and I will kill you” – and murders his way across Paris until he saves his daughter from a sheik straight out of Disney’s Aladdin. He wins back his daughter’s adoration, and gets her music lessons with the pop star he was bodyguarding for at the start of the movie.

But, of course, a movie is more than its plot. So let’s look at what makes this such a post-9/11 movie. Plenty is obvious on the surface: the special forces super soldier kicking into action to save his daughter from the ambiguously Middle Eastern bad guys (and doing so without the help of the hapless French). There’s more to it, though. As Susan Faludi noted in The Terror Dream, the American reaction to 9/11 involved trying to reinforce a particular kind of gender ideal. 9/11 was understood as a violation of the American domicile: the household inhabited by mother, father, and 2.3 children.

In reaction to this “violated domicile,” there was a cultural move to not just restore men to the forefront but restore the “paterfamilias”, the father-protector of the family who led and provided for the domicile. As Faludi notes, news pundits heralded 9/11 as an outright refutation of feminism: women in leadership had displaced (or worse) the manly men who protected America, and this led to America being attacked.[2] Donald Rumsfeld heralded the return of “heroes,” great men who would not just defend the US but restore its (gendered) order.[3] America’s opinion-makers agreed: the male id needed to be unleashed so that men could re-take their position as leaders and defenders of the family order.[4]

All of this is not just found in Taken, but is essential to making it what it is. Mills, the ex-special forces guy, has been left adrift after his skills were no longer needed in the 90s peace. His ex-wife has decided that he’s a relic and left him for a soft, suburban man. The vaguely-ethnic bad guys upset the domicile by kidnapping his daughter; the fight is ultimately over control of his daughter, with the looming threat of her being sold as a sex slave to the Sheik. The movie ends, of course, with Mills heroically killing all the bad guys, winning back his daughter, and restoring the domicile.

Looking at Taken as a genre, then, isn’t just about the plot. It’s about Taken as a story of restoring order to a violated domicile by setting out into a dangerous and foreign world. And it’s all of that as part of the US’ collective emotional response to 9/11.

What I want to do now is look at three movies – The Grey, John Wick, and Pig – which show some of the interesting directions Takens have gone. These are far from the only instances, but they show the different directions the genre can go. And, from afar, can even show how the US has culturally developed since 9/11.

The Grey

The place to start is with The Grey, a movie released shortly enough after Taken that it not only starred Liam Neeson but was marketed as “Taken with wolves.” Neeson plays John Ottway, a hunter mourning the death of his wife, and who has to chaperone survivors to safety after their small plane crashes in the Alaskan wilderness. Their mission is made more difficult by the fact that they are pursued by a pack of hungry wolves.

There are some obvious differences, of course – here Ottway is leading a group of people, not retrieving his daughter – but the similarities are significant. Ottway’s character is defined by the tragic shattering of the domicile and he plays the paterfamilias-protector character going through a dangerous foreign land (in this case the wilderness). His motivation is to restore the domicile and playing the paterfamilias in the woods is his way of achieving that.

Where Taken is a glorious story of revenge and restoration, The Grey confronts the absurdity of death. Each human has a corresponding wolf, and the humans’ deaths are absurd and meaningless. The characters die when urinating, falling, slipping near a river. And each of these tragedies are, importantly, irreversible. Ottway’s character arc is about coming to terms with the meaninglessness of his wife’s death, and accepting that there really is nothing he can do.

In the acceptance of tragedy, it becomes clear how The Grey stands relative to Taken. The Grey takes the tragic shock of 9/11 and begins the process of reckoning with the fact that there maybe isn’t any greater justice to be had, and there’s no way to put back together what was broken. There’s no saving and reuniting the family; Ottway’s wife is dead and there’s nothing he can do about that. This is what makes The Grey a 'Taken', then. Not that it’s “Taken with wolves”, but because it takes the story, themes, and context of Taken, and uses them to make a new movie that has to be understood in the context of the original.

John Wick

The next Taken I want to look at has Keanu Reeves as the titular Wick, and came deep into the Obama era.

The plot is that Wick is a former super assassin who retired to marry and settle down. The story starts shortly after his wife has died; she had bought him a dog by which to remember her. A gang of criminals kills the dog while stealing Wick’s car, causing Wick to (literally) dig up his old assassins’ tools and go on a mission of revenge through an elaborately-imagined criminal underworld. This story is pointedly psychological, and is frequently read as a return to addiction. Wick got clean for his wife, and now he’s relapsing. So what makes this a Taken?

For one, this is a story of Wick, the man of his house, going on a mission of revenge after his domicile is violated. The dog is presented as his last connection to his wife, so in killing it, the villains are not just invading Wick’s house but tearing apart the nuclear family. The dangerous foreign land in this movie is a fantastical criminal underworld, complete with gold coins, codes of honour, and secret institutions. And it is pointedly very dangerous: anyone and everyone could be a secret assassin.

But where Taken and The Grey are deeply interested in politics, John Wick represents a retreat from politics into the psychological. As Graeber argues in The Utopia of Rules, this was typical of many superhero movies of the era, where the personal becomes subordinate to the personal and psychological.[5] Taking The Dark Knight Rises as an example, Graeber notes how a story about a revolution in Gotham City – where Occupy-coded anarchist-terrorists take over the city and entomb the cops – is ultimately about Bruce Wayne the person learning to have healthy relationships with others.[6] Despite using political images, the movie is not actually interested in revolution or justice or any other part of politics. That’s all window dressing for Bruce Wayne delving into his psyche.

Similar to The Dark Knight Rises, the fantastical criminal underworld of John Wick is merely flavour for the character Wick’s personal journey. The bad guys are still vaguely ethnic, but there is no symbolism or any other importance to their ethnicity. There’s no real politics of the household, with the domicile instead representing Wick’s personal normalcy. The dog represents his own personal health more than it does any familial integrity: by the end of the movie the dog is replaced, the new dog indicating that he’s at peace once again.

John Wick, then, isn’t a response to Taken like The Grey is. Rather, it’s a Taken for its era. It’s what happens when Taken is removed from the extremely politically-conscious, post-9/11 period, and re-created in an era where a sufficient number of people were no longer really paying attention to politics. The political world is gone. The social world is gone. John Wick is a Taken where the conflict is entirely within the individual.

Pig

Pig gives us Nicolas Cage as Robin Feld, a grieving hermit. Like The Grey it confronts the inevitability of death, but moves from the context of 9/11 to climate change. It combines grieving what has been lost with grieving what will be lost.

Feld – at first just “Rob” – lives in a small shack in the Oregon woods with his truffle pig, where he trades truffles to a luxury foods supplier, Amir, for baking supplies. One night people break in and steal his pig; he teams up with Amir to head into the city to retrieve it.

We learn of Feld’s past as an elite chef, and the dark underbelly of the luxury restaurant world. While Pig keeps the revenge structure of the other Takens, as Feld moves through his old foes, he pointedly avoids taking revenge. This culminates in a ‘showdown’ with Amir’s father Darius – the pig thief – where Feld recreates a meal he had previously cooked for Darius and his wife.

While not a man of violence like Mills or Wick, Rob is still the paterfamilias of a broken home. His home has fallen apart through him losing his wife and now his pig. Both Portland and the restaurant scene play the role of the dangerous foreign land. Rob even has Wick’s secret stash, though for him it’s strategically stored luxury ingredients.

The story centres on grief. At the beginning of the film Feld tries and fails to listen to a recording his late wife made for him. Amir’s mother, Darius’s wife, is in a comatose state but neither Amir or Darius can fully let go. Rob and Amir talk about catastrophe – tidal waves and eruptions – and how there’s no way to escape them. At the end of the movie they have an exchange about how if they’d never gone to look for the titular pig, Rob could’ve lived out his life imagining the pig was still alive. “Maybe,” he says, “but she’d still be dead.”

As with The Grey, this is a story about a nuclear family that cannot be put back together. Feld’s wife is dead, his pig is dead; he goes by his old house and the persimmon tree is gone. But for Pig, these things were always transient.

In Pig, everything is transient. A meal, of course, is an experience which immediately disappears into the past. Feld counsels a luxury chef who has abandoned his dream of running an English pub: “Every day you wake up and there will be less of you.” The time he’s invested in his restaurant has been spent wrongly. Even cities are temporary, Portland doomed to be destroyed by tidal wave, earthquake and volcano.

But we have what we value, and memory lets us hold on to what we value. Feld is able to return to his wife’s cassette. The meal lets Darius not only remember his wife but return to the good that he had with her. Even the discussion about the end of Portland ends with a mutual vow between Rob and Amir:

“Well I’m not fucking moving to Seattle.”

“Fuck Seattle.”

In its focus on transience, Pig is very much a Taken for a world that has moved from terrorism to climate change as the foremost imagined threat. Feld’s pig was stolen, but the biggest threat of the movie is the persistent decay of time of passing. This is a world where everything is coming to an end, and the only thing you can do is salvage what good you can in the time you have.

The foreign world, too, is not dangerous in its potential to be harmful but in how it represents the wrong paths in life. Pursuing power, fame, and money as superficial signifiers of status instead of finding what’s truly valuable.

Looking at Taken as a genre, then, isn’t just about the plot. It’s about Taken as a story about restoring order to a violated domicile by setting out into a dangerous and foreign world.

These are just a few standout examples of Takens. They show the different direction the genre has gone. Regular Takens are still being made, even starring Liam Neeson.[7] The world, America especially, still loves its murder-dads murdering the family back together.

But looking at these examples gives us a way to understand (one) way the US has developed after 9/11. We begin with murdering the family back together, we move on to confronting the absurdity of death. With John Wick the story turns inwards, and lastly with Pig we get a connection to new political themes.

The transition of movies away from explicitly interrogating the meaning of 9/11 doesn’t mean that Taken is going to be left in the dust. There are still reasons to understand the US as a society reacting to 9/11. And, so long as that’s the case, there will be new Takens to be had.

[1] Stacie Friend, Fiction as a Genre, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 112/2 (2012), pp. 179-209.

[2] Susan Faludi, The Terror Dream, (New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 2007), pp. 20-1.

[3] Faludi, pp. 46-47.

[4] Faludi, pp. 77-78.

[5] David Graeber, The Utopia of Rules, (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2015), pp. 220-221.

[6] Graeber, pp. 222-223.

[7] Both The Ice Road and The Marksman were released in 2021.

References

- Faludi, Susan. The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post-9/11 America (New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 2007).

- Friend, Stacie. Fiction as a Genre, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 112/2 (2012), pp. 179-209.

- Graeber, David. The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2015).

Further Reading

For more of the cultural influences that went in to Taken, nothing comes close to The Terror Dream by Faludi (see above). The book was actually published before Taken was released, so you can think of the movie as a successful prediction by Faludi.

No comments

Start the conversation…