Bioware & Voluntary Slavery

A recurring theme in Bioware’s RPGs is the idea that slavery – while bad – can be justified if it’s chosen. Throughout the Dragon Age games, for instance, we learn that in the Tevinter Empire, slavery is legal. Many slaves are captured from other regions of Thedas, but additionally,

Free people may choose to sell themselves into slavery to provide for their families. Those slaves who are purchased by the Imperium itself rather than private individuals are called Servus Publicus, or state-owned slaves…[1]

In Dragon Age: Inquisition, a codex entry notes of the servus publicus that they “do all the tasks proper citizens will not.”[2] Tevinter mage and oft-beloved party member Dorian paints a rosier picture:

Dorian: In the south you have alienages, slums both alien and elven. The desperate have no way out. Back home, a poor man can sell himself. As a slave he could have a position of respect, comfort, and could even support a family. Some slaves are treated poorly, it’s true, but do you honestly think inescapable poverty is better?

Inquisitor: At least they’re free. They don’t have slavery forced on them.

Dorian: You think people choose to be poor and oppressed? I doubt it…

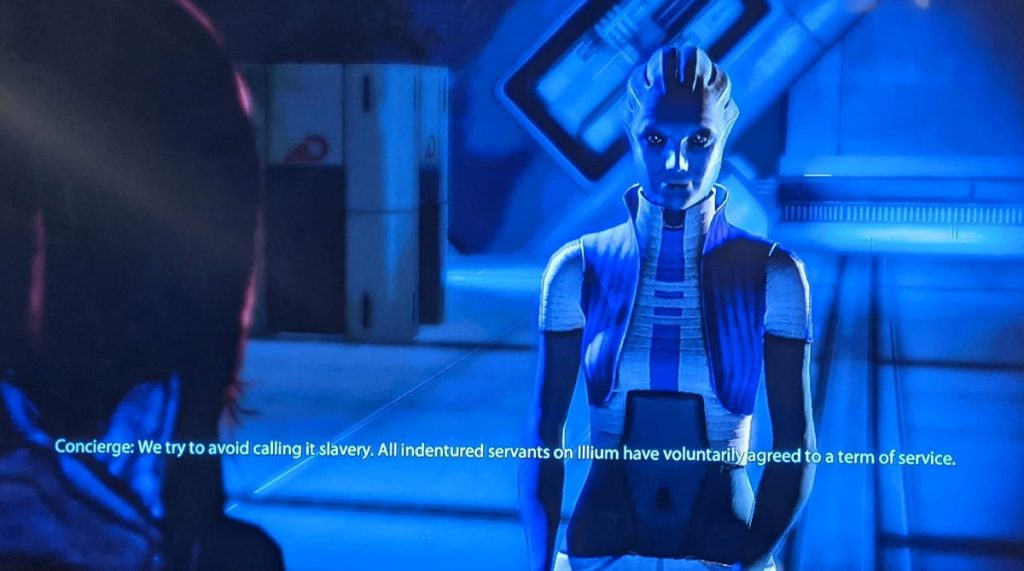

A similar conversation crops up in Mass Effect 2 on the planet Illium:

Shepard: I can’t believe an asari world would allow slavery!

Concierge: We try to avoid calling it slavery. All indentured servants on Illium have voluntarily agreed to a term of service. Most choose indentured service as a means to pay off debt or avoid imprisonment. A contract holder is responsible for the well-being of her servants, and a servant’s duties are agreed upon before the contract is signed.

The reality is less sanitised – as the player walks around Illium, an ad for a company called ‘IndentureTech’ plays in the background:

You’ve been a slave to your employees for too long. Shouldn’t it be the other way round?

In these examples, enforced slavery is distinguished from voluntary slavery. In what follows, we consider whether volunteering makes a moral difference.

For the purpose of our discussion, we can ask of the Bioware examples two questions:

- Do these examples ‘count’ as slavery?

- Does the putative voluntariness make a difference?

With regards to (1), one possible response is that indentured servitude standardly comes with limiting conditions built-in: you have to work to pay back x amount of money, or for y years, or until z event. Looked at this way, indentured servitude might be thought of as being more like an exceptionally onerous employment contract than like slavery – there are difficult conditions attached to escaping them, but it’s possible (by design). The indentured servant gives ten years’ service and is free; the volunteer army recruit gives three (or five, or seven) years’ service and is free. It’s not even unusual for there to be very punitive clauses dealing with what happens if the contract’s broken. So perhaps we should just think of indentured servitude as being high-risk (and, uh, low-reward) employment: if you don’t want to take the risk, don’t take the job. The invisible hand of the market solves the problem once again!

Well, no. As it happens, there are good reasons to think of lots of modern employment contracts as forms of indentured servitude, including the ones given above – but that just means that many more people are in effect in servitude than we usually think.[3] This isn’t quite to re-assert the old claim that wage labour is slave labour, but it should make us wary of going “well really it’s just like being a wage labourer under capitalism, so obviously indentured servitude isn’t like slavery”.[4] Rather, it should suggest to us that if there is a relevant distinction between waged labour, indentured servitude, and slavery, it’s not (or not primarily) to do with how difficult it is to escape the respective conditions or even the consequences of doing so.

Instead, we might think the crucial difference is to do with power and power structures: specifically, the extent to which one’s freedom or ability to do otherwise than the boss says is a matter of structural power (im)balances. Let’s take two simplified cases.

Case 1: Kim Kitsuragi is employed by RCM as a police lieutenant. There are certain restrictions on what Kim may do at work, and on how many hours a week Kim can spend out of work. These restrictions are built into Kim’s contract.

Case 2: Crypti is a slave on a cocaine plantation on the Irmalan Plateau. There are restrictions on what Crypti may do at work, and how many hours a week Crypti can spend out of work; there are also restrictions on where Crypti may live, who they may see, probably who they may have intimate relationships or children with. These restrictions may or may not be formalised.

Crypti is situated such that by design their life is vulnerable to arbitrary interference at the whim of another – in the philosophical jargon, they’re dominated (see Pettit 1996; 1997). It’s not just that somebody could interfere with their life, it’s that the social structures they inhabit are designed to make this possible. Conversely, the social structures that Kim inhabits are designed to limit how much his employer can interfere with his life. These structures might be – are likely to be – imperfect.[5] Still, their explicit goal is to make sure that Kim is able to make his own decisions not only about how to do his job, but more importantly whether or not to do his job at all. Kim is non-dominated, while Crypti is dominated – and they seem to be dominated in just the way that the people in the Bioware examples are dominated (a servus publicus cannot choose to become a merchant instead).

So we have reason to think that Tevinter and IndentureTech are indeed engaging in slavery, and can turn to the second question: Does volunteering make a difference?

To answer this question, it helps to think about autonomy. What you conclude will depend on whether you think of autonomy primarily as a matter of knowing what you want to do; of doing what you want to do with your life; or of being able to control how your life goes.[6] Let’s consider each of these in turn.

Taking the first line, we find people like Frankfurt (1971) and Dworkin (1976; 1981). According to them, autonomy is – very roughly – a matter of endorsing your first-order desires at a higher-order level. Say you have some first-order, world-facing desire, like “I want a pint”. If you want this desire to be effective – if you endorse its efficacy at a higher-order level – then according to them you’re autonomous. Under this view autonomy is a psychological matter, one to do with the efficacy of the “deep” or “true” self over its first-order desires. So long as the enslaved agent continues to endorse those desires that point them in the direction of slavery, it is indeed conceptually possible to be an autonomous slave.[7]

Regardless of whether you think this is convincing in the slave case, there are reasons to be suspicious of structuralist views. Suppose that a Tevinter woman becomes a servus publicus, reasoning that it is the best (and perhaps only) way to save her family from poverty, but feels considerable grief at the loss of her former freedom. In other words, she has a first-order desire to be free, but endorses her servitude at a higher-order level. Marilyn Friedman (1986: 31) pointed out that on views like Frankfurt’s and Dworkin’s, the servus publicus would be made more autonomous by rejecting

“her frustration grief and depression, and the motivations to change her life which spring from these sources…[and which] may be her only reliable guides.”[8]

That is, supposing that she still endorses the servitude, still “wants to want” to be a good servant, then under the structuralist model she would become more autonomous by squashing the desire to chib the overseer, set fire to the big house and run like hell for a less constrained life. This seems – to use the technical term – exactly bass-ackwards to Friedman. Thinking about why might be illuminating.

Generally, we think of autonomous agents as not merely knowing (more or less) what they want out of life, but also being able (more or less) to get it. In Friedman-type cases, though, it seems not only that you can become more autonomous by subordinating what you want to some pre-existent conception of what you should want, but also that whether you get what you want is irrelevant to whether you’re autonomous.

“You think people choose to be poor and oppressed? I doubt it…”

A response might be to invoke what’s called procedural independence, in other words, that how you form your desires is important too. The procedural independence theorist is likely to say of the voluntary slave that something is amiss with how they’ve formed the desires to be subservient – faced with the choice between slavery or starvation, the person is making choices that, because of the pressure, don’t represent who they “really” are. This may well be true in lots of cases, but i) we ought to be careful of suggesting that people aren’t competent over their own desires, and ii) it still doesn’t evade the problem that so long as your desires line up right - or have been/can be subjected to critical thought - whether they’re met doesn’t matter for autonomy. This seems weird considering that “living a life of one’s own” is near-as-damnit the one-line gloss on what it is to be autonomous.

“Aha!” say proponents of what’re sometimes called the self-authorship family of views, “precisely! In these cases, your desires might represent the real you, but your life isn’t the life that you want, and so you’re not autonomous”. According to them, to be autonomous is to “decide for [yourself] what is valuable, and to live [your] life in accordance with that decision” (Colburn, 2010). On this view, so long as the agent has thought carefully and critically about what they want, then they are autonomous insofar as they get what they want. The same will apply for the person who wants to be enslaved. Again, almost nobody thinks that this is likely, but it’s a conceptual possibility: it is possible to be an autonomous slave, if the life of slavery is consistent with your decisions about what is valuable.

And, obviously, this explains why voluntariness is important: if you choose to x, under conditions of procedural independence, then it seems fairly safe to say that x-ing represents what you want out of life – that you’ve decided for yourself that x is valuable, and can now live in accordance with that decision. Under the views we’ve so far considered, then, the IndentureTech employee and the servus publicus could be autonomous, although it’s unlikely.

The relational view offers a different analysis.[9] On this view, what it is to be autonomous is to be (more or less) in control of your life – to be socially situated such that your desires about life are taken seriously precisely because they’re your desires, and that you are able to pursue these desires. In other words, to be authoritative and powerful over the direction of your life. Someone who’s enslaved is not powerful over the direction of their life; definitionally, they’re vulnerable to interference at the whims of another.[10] Under a relational account, then, the slave isn’t autonomous.

"You’ve been a slave to your employees for too long. Shouldn’t it be the other way round?"

Interestingly, this means that voluntariness doesn’t make a difference: you may very well have been autonomous when you decided to commit yourself to slavery, but once that’s happened you aren’t any longer. Imagine that you freely decide to be tied up. Once you’ve made the decision, your movements are restricted, and the duration of the restriction is now out of your control – hopefully you’ll be released if you ask to be, but you’re much more vulnerable than you were before the binding. Likewise, the servus publicus might have freely sold themselves, but can’t then change their mind and become a hairdresser instead.

That’s not to say that voluntariness doesn’t matter for relational theories. It’s clearly important for being powerful and authoritative that your choices are taken seriously, and so voluntariness is important. But it’s not a sufficient condition for autonomy – it’s not enough. Merely wanting to do something doesn’t mean that doing it makes you autonomous. Autonomy relationally construed is a social phenomenon, and so – perhaps counterintuitively – we’ve got really strong reasons to prevent some kinds of relations from obtaining. Voluntary or no, your boss having near-untrammelled power over how your life goes is not consistent with your being able to decide how your life goes.

As Dorian notes, “Abuse heaped on those without power isn’t limited” to slavery. But choosing slavery doesn’t mean that what’s ‘heaped on’ isn’t abuse.

Footnotes

[1] https://dragonage.fandom.com/wiki/Slavery

[2] An in-game Codex entry, attributed to In Pursuit of Knowledge: The Travels of a Chantry Scholar by Brother Genitivi. Full text available at https://dragonage.fandom.com/wiki/Codex_entry:_Tevinter_Society.

[3] You’ll have noticed, for example, that “don’t take the job” is real easy advice to dispense from a comfy armchair, but carries all the heft of a gnat’s fart if taking the job is the only alternative to penury and starvation.

[4] Cohen (1982) draws this queasy parallel, though he does at least admit that he probably ought not to be equating wage labour and chattel slavery.

[5] That’s why you should join a union. Go on, I’ll wait.

[6] But wait, aren’t these last two the same thing? No, as <takes hold of tablecloth meaningfully> I’ll go on to suggest.

[7] I should add that neither of them think this is especially likely, though.

[8] Friedman’s original example refers to someone confronting internalised misogynistic norms regarding “a woman’s place”.

[9] Strictly, the constitutive social-relational view. See Oshana (1998; 2006).

[10] I also think that enslavement relations must deny the authority of the agent, but we can leave that aside.

References:

- Cohen, G. The Structure of Proletarian Unfreedom, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 12:1 (1983), pp. 3-33.

- Colburn, B. Autonomy and Liberalism (Routledge: New York, 2010).

- Dworkin, G. Autonomy and Behavior Control, The Hastings Center Report, 6:1 (1976), pp. 23-28.

- Frankfurt, H. Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person, Journal of Philosophy, 68:1 (1971), pp. 5-20.

- Friedman, M. Autonomy and the Split-Level Self, Southern Journal of Philosophy, 24:1 (1986), pp. 19-35.

- Oshana, M. Personal Autonomy and Society, Journal of Social Philosophy, 29:1 (1998), pp. 81-102.

- Oshana, M. Personal Autonomy in Society (Ashgate: Aldershot, 2006).

- Pettit, P. Freedom as Anti-Power, Ethics, 106:3 (1996).

- Pettit, P. Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government (Oxford University Press: New York, 1997).

Further Reading

For more examples of in-text justifications for slavery, check out the TV Tropes page on "Happiness in Slavery".

To learn more about philosophical accounts of autonomy, you could start with the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entries on autonomy in moral and political philosophy and feminist perspectives on autonomy.

1 comment

A webcomic I read, Leif and Thorn, is a good example of how to do this better in my opinion. Leif is an indentured servant though NOT a slave as he mistakenly says during his initial training. He has an identifying tattoo with a chip in it that literally zaps him if he thinks or says the wrong thing. Which feels like a literal symbol of the lack of freedom he has. He does have some freedom- he can see his boyfriend and go out (with permission). It does cost money from anyone “renting” him which partially pays down his debt.

He doesn’t have a choice in entering due to him paying off an unknown crime his parents committed. You could say he was sold in a sense? He definitely didn’t volunteer but was willing at first since it was his duty. In the beginning, he doesn’t want to leave at all because of brainwashing and guilt for his parents’ crime, which as their child he feels responsible for. But later he begins to question this and begins to feel more trapped and understand the system itself is unfair. So if I understand these theories right he potentially begins to lose autonomy as he becomes less willing to be a slave OR never had it at all?

Overall I think it does a good job of outlining how even though he has the ability to leave he’s trapped. He IS a slave, with freedoms given in a restricted way but he generally has no choice. Plus many of the other characters do recognize how rotten the system is, unlike the other examples. It’s considered a human rights issue. So that alone gives it a more even representation.

Apologies for how long this is, I seem to have written an essay of my own… I think these comparisons are relevant but I’m also not a sociologist.