Trope Alert: Moral Warping

I’ve always been interested in how superhero movies present the battle between good and evil. The (usually titular) superhero isn’t just the goodie but the goodie for some particular reason. Maybe they represent some important set of values, or perhaps fight to defend a vision of society. The villain opposing the superhero also represents something, maybe an opposing set of values or a dark reflection of the hero. Through this opposition the film constructs a kind of moral world: a vision of what is good and what is bad, at least within the film.

Sometimes, constructing the moral world doesn’t go smoothly. Maybe the hero doesn’t seem to stand for anything good, and so there’s no reason to accept them as the hero. Or perhaps the villain isn’t especially villainous; a sympathetic villain is common enough but something about this character makes it seem like they’re just straightforwardly in the right. There are a few ways a film can deal with this problem. One is to just ignore it and power through, in which case you end up with a thematically-unmotivated conflict. Another is to try and embrace a bad hero or good villain, and end up with a movie espousing some ugly values. I want to talk about a third option, which I call moral warping.

Moral warping is a kind of thematic narrative contrivance, where a character (usually a designated villain) does something out of line with other elements of their characterisation for the sake of making the character conform with their designated role as hero or villain. More specifically, we can think of moral warping as happening when:

- A character is given a set of motivations and values which define that character’s role in the story, and

- Those motivations and values seem to dictate a moral role in the story (goodie or baddie), other than the moral role that character actually has, and

- The character does something to bring them in to line with their moral role, and

- Importantly, this thing they do to bring them back in to line with their role does not seem to flow from, fit with, or otherwise be reconciled with their initial defining motivations and values.

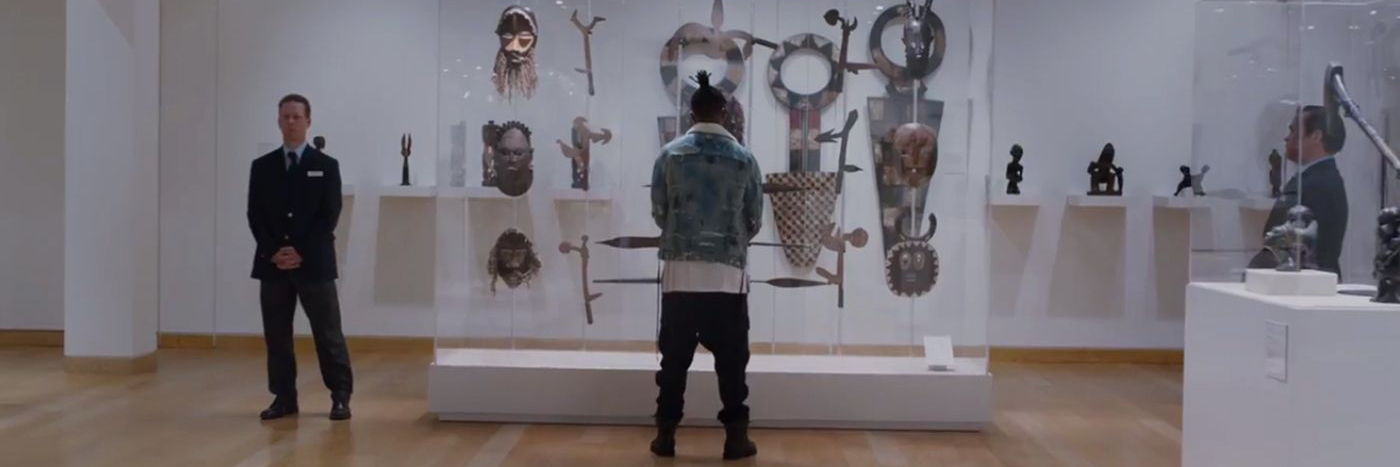

A good first example for moral warping is Marvel’s Black Panther (2018) and the character of Killmonger. He is introduced in a British museum, correcting the curator about the provenance of stolen artefacts. His origin story is that he was abandoned in Oakland by the Wakandan King T’Chaka after his father became too sympathetic to the Black liberation movement, returns to Wakanda to challenge for political leadership through the politically-recognized method of trial by combat, eliminates the magic herb which sustains the monarchy (declaring himself to be the last king), and states his motivation to be the end of Black oppression worldwide. This motivation obviously resonated with many people, leading to the meme, hashtag, and any number of articles titled “Killmonger was right.”[1]

Of course, this is only a partial description of the character. Through the movie we are given reasons to think he is not really motivated by liberation. Rather, he is motivated by spite and revenge. Revenge against the royal family for abandoning him, and spite at having had to live in the US rather than Wakanda’s techno-utopia. He suffuses his mission to ship weapons to Black liberation movements with the language of the British empire, promising that the “Sun will never set” on Wakanda.

Moral warping is a kind of thematic narrative contrivance... for the sake of making the character conform with their designated role as hero or villain.

It is easy to see how Killmonger might be subject to moral warping. The character is fundamentally presented as an anti-colonial revolutionary, opposing oppression worldwide, only for that to be undercut by the revelation that he’s just a psychologically-hurt would-be oppressor. This sort of warping is easy for audiences to spot and instinctively unskew because the idea that revolutionaries are just psychologically hurt is nothing new. As Tommy Curry has shown, the idea that Black men are motivated by a simultaneous desire to replicate white oppression while rejecting white values has a long history in the United States.[2] If the badness of Killmonger’s character is a common slander against Black revolutionaries, it’s easy to mentally class the character’s badness as not fully real. The bad acts are discounted, and Killmonger remains understood as a real revolutionary.

However, despite Killmonger’s badness being a common slander, his badness still fits with his character. The moral world of the Marvel Cinematic Universe is defined, in part, by the goodness of hierarchical power structures that isolate power in the hands of a few great people, and the fundamental goodness of the status quo.

(Even when the baddies have control of the status quo this is presented as a problem of infection. Get rid of the baddies and all is well, no need to change how the system actually works. The most extreme case of this is in Captain America: the Winter Soldier where it is revealed that the entire American military and security apparatus has been overtaken by a HYDRA (effectively super Nazis) conspiracy. Once the HYDRA agents are vanquished, the heroes simply take back control of the apparatus.)

In the context of the movie’s moral world, his desires for global revolution and an end to the monarchy were always bad. The character’s villainy is, within the movie’s moral world, continuous with his initial characterization. This is, after all, a movie whose climactic action set piece involves a CIA officer operating military drones to help the rightfully-deposed King T’Challa retake power through a coup. Altogether, then, the character of Killmonger is less a case of moral warping than it is of the movie simply having ugly values.

A better example is found in the previous year’s Marvel offering, Spiderman: Homecoming. Here, the villain is Adrian Toomes, AKA the Vulture. Toomes is a former construction contractor who loses his business after Tony Stark uses his government connections to take over a number of reconstruction projects after the events of Avengers: Assemble (2012). Driven to desperation, Toomes and his construction crew turn to stealing alien technology and selling it as weapons.

Unlike with Killmonger, there isn’t a thematic through line from a construction contractor and father figure disrupted by government corruption to weapons dealer. Rather, Toomes’ criminality seems to be entirely motivated by the need to set him up as a foil for Tony Stark. What’s important here – and what makes this a true case of moral warping – is that absent Toomes stealing and selling weapons, there is nothing in Toomes’ characterization that would make him a baddie.

Toomes’ character, while not as well-developed as Killmonger, still manages to reflect interesting ideas. For example, it’s striking for how closely it matches the subject of China Miéville’s short story Scrap-Iron Man.[3] In that story, a collective of workers discarded during the 2008 economic downturn put together a suit of scrap metal and set off to fight Tony Stark for being one of the billionaires who rendered their hometown destitute. The characters, like Toomes’ Vulture, are laid off construction workers, build their own armour from scraps, and have a conflict with Tony Stark for being the author of their destitution. The characters represent the same symbols, have the same enemies, and have at least similar motivations. However Toomes must be a villain, and Stark a hero, so Toomes arbitrarily does evil. The character is warped into a villain so that he fits within the movie’s moral world.

Footnotes

[1] A brief sampling: Lynette Monroe, Black Panther Analysis: Was Killmonger Right?, The Charleston Chronicle; Killmonger was Right: How the Black Panther’s Villian Stole the Show, Complex News; BFoundAPen, Killmonger was Right, Medium. And then there are articles that took the idea as a jumping off point: Adam Serwer, The Tragedy of Erik Killmonger, The Atlantic; Justin Charity and Micah Peters, How Do You Solves a Problem Like Wakanda?, The Ringer.

[2] Tommy J Curry, The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood, Temple University Press (2017).

[3] China Miéville, Rejected Pitch, Rejectamentalist Manifesto. Posted April 7, 2011.

References

- Curry, Tommy J. The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood (Temple University Press, 2017).

- Miéville, China. Rejected Pitch, Rejectamentalist Manifesto (2011). https://chinamieville.net/post/4406165249/rejected-pitch

Further Viewing

If you want more media with moral warping, Iron Man 2’s Ivan Vanko is another victim turned evil to affirm Tony Stark’s goodness.

There are also movies which engage moral warping head on. Disney’s Maleficent asks what the titular character might be if she wasn’t forced to be the ‘wicked woman’ in Sleeping Beauty, while X-Men: First Class examines a moral world where Magneto’s radicalism is in the right and Charles Xavier’s liberalism is a kind of complicity.

No comments

Start the conversation…