Mass Effect & the Problem of Other Minds

I’ve been thinking about the problem of other minds. I take it that – telepaths aside, and rightly or wrongly – we tend to think of our minds[1] as private: there is a type of access that only I have to my mental states. Only I can know quite what my experiences are like: what it is like for me to feel the squish of a lone grape trapped between my unsuspecting foot and the kitchen floor, the particular depth and timbre of the sorrow experienced by a much younger me upon reaching the end of The Amber Spyglass, or the heady joy at all ages from almost anything involving glitter.

Nonetheless, I normally think that the rest of you have minds too, and sometimes I even think I can know what’s going on in that mind of yours. I can’t peer into it, but based on your behaviour, and by analogy to my own experience, I predict what you’ll do, respond to how I think you’re feeling, and so on. Presumably you do that too. After all, if you don’t have a mind – if you don’t feel, or think, or want, or believe – then my efforts to ensure I’ve stocked up on your favourite tea before you visit seem rather pointless. The attribution of minds and mental states to others is ubiquitous: here are a couple of examples from Zusak’s The Messenger[2] (emphasis mine):

She looks up at me, and for a moment, we both get lost in each other. She wonders who I am, but only for a split second. Then, with stunning realisation clambering across her face, she smiles at me.[3]

[...] He’s still groggy but his eyes grow wide. He thinks about a sudden movement but understands very quickly that he can barely pull himself out of the car.[4]

The problem of other minds is an epistemic one: how are we justified in attributing mental states to others, given the possibility that their minds may be very different to our own, if they have them at all? How can we know that others have minds, and what are they like?

These are questions too big for a single article, so here I just want to highlight two things: firstly, that we do attribute minds and mental states to others (whether or not we are justified in doing so, or whether we can know that they have them); and secondly that one argument for doing so is, as I hinted at above, the argument from analogy.[5] Even if I don’t know what your mind is like (or even if you have one), can’t I still reasonably suppose that your mental life is much like mine? Can’t I use myself as a model for you and everybody else?

This sort of argument was put forward by John Stuart Mill and Bertrand Russell, among others. Here’s Mill’s version:

I conclude that other human beings have feelings like me, because, first, they have bodies like me, which I know in my own case to be the antecedent condition of feelings; and because, secondly, they exhibit the acts, and other outward signs, which in my own case I know by experience to be caused by feelings.[6]

Of course, there are always problems with induction from one case, and one case is all we have, as my mind is the only mind I can be sure about. So, there’s a difference between a generalisation like ‘If a person exhibits human behaviour then they have a mind’ and ‘If you encounter a koala in the wild then you’re in Australia’, because in the latter case we have lots of evidence it’s true (there are lots of instances of people encountering koalas in the wild, and all have taken place in Australia)[7] and in the former I only have on instance: me!

If I was the only philosopher you had ever met, you might come to think that all philosophers were 5ft2, interested in time travel and spoke with an Aussie Accent...

The reality is sorely disappointing.

Can’t I use myself as a model for you and everybody else?

As Simon Blackburn puts it,

The mere fact that in one case – my own – perhaps as luck has it, there is a mental life of a particular, definite kind, associated with a brain and a body, seems to be very flimsy ground for supposing that there is just the same association in all the other cases.

If I have a box and it has a beetle in it, that gives me only very poor grounds for supposing that everyone else with a box has a beetle in it as well.

Perhaps worse, it gives me very poor grounds for denying that there are beetles anywhere else than in boxes.

Maybe then things that are very different from you and me physically are conscious in just the way that I am: rocks or flowers, for example.[8]

Even if we can move past this worry, there’s another: even if the argument from analogy works for people similar to me, what about creatures who are dissimilar? And how different is too different: people with behaviour or bodies different to mine? Animals? Aliens?

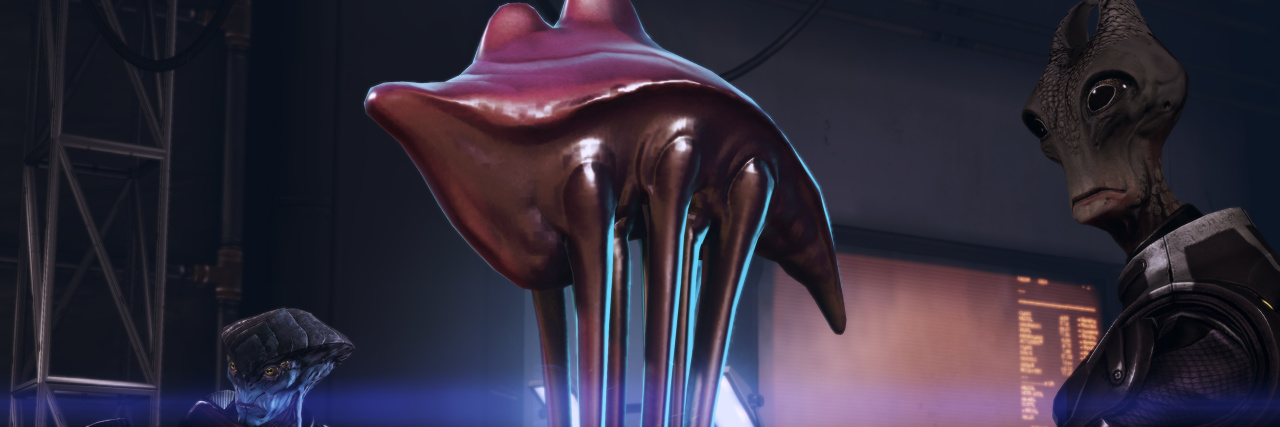

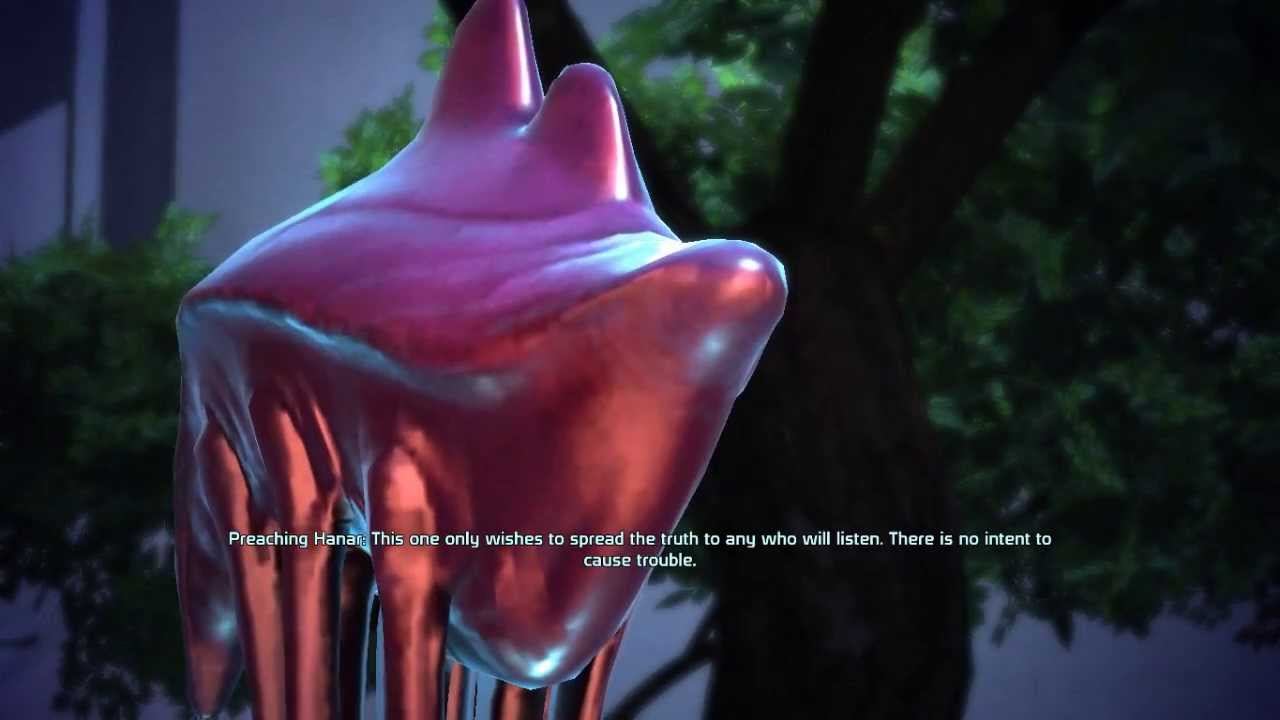

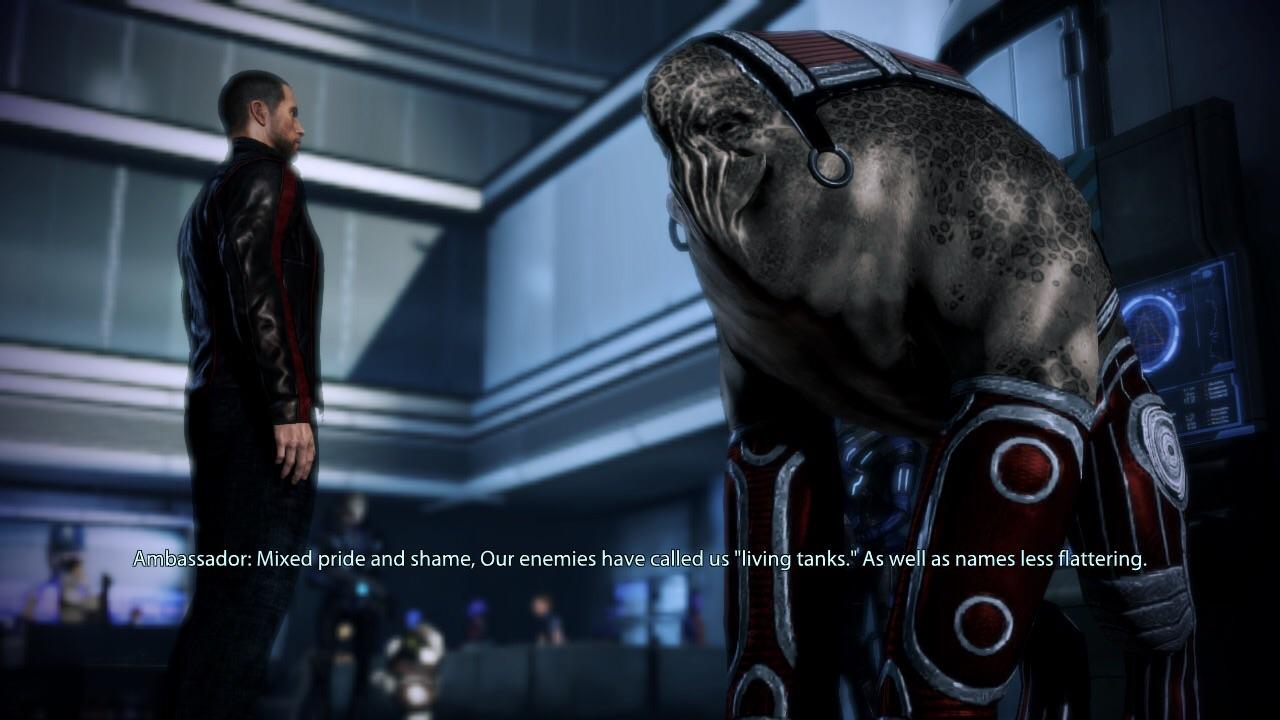

And thus we arrive at Mass Effect. One of the things I like most about the series are the aliens. Less the humanoid aliens – although they’re fun too – but the truly alien aliens. Two are particularly of note (I’m borrowing the descriptions of TVTropers for these, as they’re priceless). First there are the Hanar, who

look something like dog-sized pink jellyfish with seven feet long tentacles, speak through bioluminescence (using Translator Microbes to communicate with other species), and have the tendency to refer to themselves as “This one” (because to the hanar, using one’s name in public is egotistical).[9]

The elcor, by contrast,

resemble elephants without trunks that have been crossed with gorillas and stand about two metres tall at the shoulder. As their communication relies heavily on body language and pheromones (both too subtle for other species to decipher), they lack the ability to talk in anything but a flat monotone, which they compensate for by beginning their sentences by stating [their emotional states]…even when it is “With barely contained terror: Fine have it your way.”

However, except for their body size and unusual speech, they appear perfectly normal when interacting with other species.

The bodies and behaviour of the Hanar and Elcor are very different to ours – much more different than many of the aliens we see in science fiction.

Nonetheless, it seems, they think, feel, desire, believe. Putting aside their being fictional, there is presumably something it is like to be a Hanar or an Elcor. And we have reason to believe that at least some of what’s going on in their minds is similar to what goes on in ours. The Hanar merchant Opold displays concern for the impatience of one of its[10] customers, and depending on the player’s actions can become angry. A particularly devout Hanar on the citadel argues to be allowed to preach on the basis of its desire to share the truth of its Gods. The Elcor too make reference to recognisable mental states states when speaking – exasperation, shock, horror, worry, delight – in contexts where we might feel the same: concern for guards that haven’t slept, shock at someone discovering a secret, the desire to move on from one’s job to something new.

A lot of the philosophical discussion of the problem of other minds has focused on what we can conceive, what’s possible, and the link between the two. If nothing else, the Mass Effect aliens make it easier to conceive of beings very different from us that nonetheless seem to have minds and mental states, not so far removed from our own.

footnotes

[1] Whatever they might be: brains, consciousness, something over and above the physical etc.

[2] Known as I am the messenger in the USA, but my well-loved Aussie edition goes by the original title.

[3] Markus Zusak, The Messenger, p. 54

[4] ibid., p. 95

[5] It’s not the only one. For more on it or others, see https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/other-minds/#ArguAnal

[6] John Stuart Mill, An examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy, p. 243

[7] https://www.alternatehistory.com/forum/threads/silly-ahc-wild-koalas-outside-of-australia.338534/

[8] Simon Blackburn, Think, p. 55

[9] TV Tropes, Starfish Aliens/Video Games, https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/StarfishAliens/VideoGames

[10] The preferred pronoun for Hanar in public is 'it'.

References

-

Blackburn, S. Think (Oxford: OUP, 1999).

-

Mill, J. S. An examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy, 6th edition (London, 1889).

-

TV Tropes, Starfish Aliens/Video Games. https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/StarfishAliens/VideoGames (Accessed: 21/02/2020).

-

Zusak, M. The Messenger (Sydney: Pan Macmillan, 2002).

Further Reading

A good starting point is the SEP’s article on Other Minds.

Russell also offered an argument from analogy, which can be found in his Human Knowledge: Its scope and Limits (Allen & Unwin, 1948).

Finally, for more on Mass Effect aliens, see the fan wiki.

No comments

Start the conversation…