Nor Have I Yet Outrun the Sun (Part 1)

Mysterious thing, Time. Powerful, and when meddled with, dangerous.

Albus Dumbledore, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

More years ago than I’d like to admit, as an undergrad (or an ‘ickle secondie’, as Peeves might have called it), I had a paper about Harry Potter and time travel published in a small Sydney journal.[1] My philosophical ability has (I hope) improved since then, but the usefulness and interest of the text in question hasn’t diminished: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is one of only a handful of internally consistent, philosophically plausible, time travel texts – and is an exemplar of three of the main ‘paradoxes’ that arise in the time travel literature. I use it in teaching, in giving talks, and now – dear readers – I bequeath it to you.

In this series, I’ll be looking at each of the three ‘paradoxes’ in turn, and how they can be overcome (or, as Heinlein put it – in a wonderful, if underutilised, portmanteau – ‘paradoctored’).[2] But first: why all the scare quotes around ‘paradox’? Well, because it isn’t clear that all 3 of the puzzles we’re interested are strictly paradoxes, in the logical purist’s sense – they don’t involve an explicit contradiction, but rather a conclusion that strikes us as unacceptable. (I’ll avoid the punctuation from now on, unless I’m making a deliberate point.)

Paradoxes are a prime target for philosophical consideration: they’re the equivalent of an alarm or flashing red light, indicating something wrong with one’s reasoning or starting assumptions. If a given scenario or argument is paradoxical, that counts against it. Many of the arguments against the possibility of time travel employ the idea that time travel and its consequences are paradoxical.

For example, if I could travel back in time, it seems I could prevent my birth (think Back to the Future, or Futurama’s Roswell that Ends Well). But if I wasn’t born, how could I go back in time? (Never fear - as we’ll see, there’s good reason to think that time travel isn’t paradoxical in this way).

So paradoxes = bad, but interesting.

Now, where are the paradoxes in Harry Potter? (And, for those of you with insufficient dedication to re-reading/re-watching the series at every opportunity – where is the time travel?) Cast your mind back to the latter chapters of Prisoner of Azkaban…[3]

Harry Potter, famous teen-wizard, is having a rather bad day. Hagrid’s hippogriff, Buckbeak, has apparently been executed…

‘Wait, wait, wait!’ I hear you exclaim. ‘APPARENTLY been executed? That’s not right, he WAS executed. And then Harry saved him. He changed the past!’ We’ll get to that. Promise. All that matters at this point is that it appears - rightly or wrongly – that Buckbeak has been executed. Let us resume.

Hagrid’s hippogriff, Buckbeak, has apparently been executed, and our hero is attacked by Dementors and possibly about to die. On the verge of unconsciousness, he sees what he believes to be his dead father, who casts a Patronus Charm to save him. He wakes up in hospital after his miraculous rescue, only to find out that his newly-discovered godfather is about to be killed.

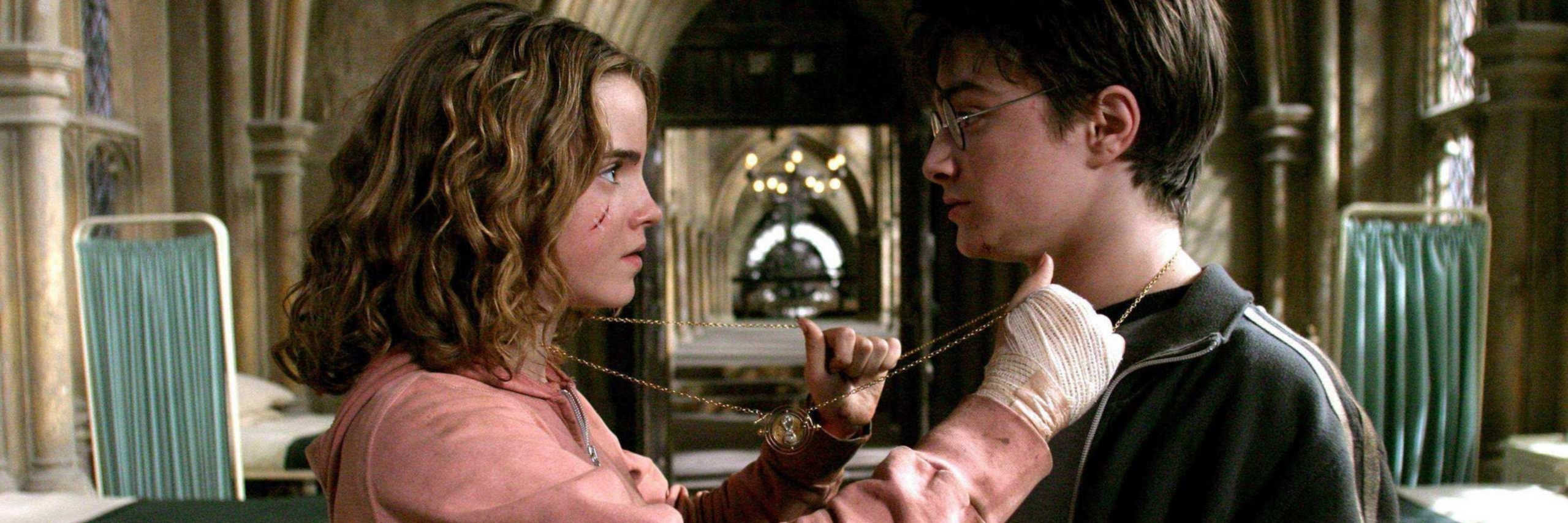

On the advice of the ever-so-wise Albus Dumbledore, Harry travels three hours back in time with his friend Hermione (who, let’s be honest, is the real hero of this story, and, interestingly, one of the very few female time travellers actually in control of the time travel device).

Our daring duo save the ill-fated hippogriff. In the hopes of seeing his dead father, Harry watches the Dementors attacking, only to realise that it was himself that he saw, and proceeds to cast the life-saving Patronus (thanks to an odd bit of logic).

(‘Is that the bit where he…?’ Yes, yes, it is. We’ll get there.)

With Buckbeak’s help, Harry and Hermione free Sirius, and return to the hospital just as their earlier selves are using the Time Turner to depart. Thus ill-fortune is averted, several lives are saved, and the novel (and accompanying film) has a dramatic climax. Voila!

And now, with memories refreshed, the paradoxes:

- Buckbeak the hippogriff appears to have been both killed and not killed.

- Harry survives to save himself because he is saved by himself.

- Harry knew he could cast the Patronus because he had “already done it.”

Paradoxes = bad, but interesting.

The first time we see the events in question, pre-time travel, Buckbeak seems to have been killed by the executioner Macnair: the golden trio hear the swish and thud of the axe, and Hagrid’s tears at the event. Post-time travel, we see Harry and Hermione save Buckbeak. Thus the following are both true – ‘Buckbeak was killed’ and ‘Buckbeak was not killed’ – and we have a (paradoxical) contradiction.

As for (2), Harry must survive the Dementor attack in order to be able to travel back in time to save himself, which leads to his survival and subsequent time travel… to save himself. The time travel seems to be ‘predestined’ by the circumstances of his survival, which leads to all sorts of questions: could he have chosen not to use the Time Turner? How can his future decisions affect whether he survives in the past?

And finally, how did Harry go about casting that Patronus? Such a charm requires a great deal of skill, far beyond the average third year, and a focus that Harry has struggled to muster in previous confrontations with the Dementors (and their Boggart mimics). This time, however, when it counts, Harry knows he can do it. Why? Because he’s already done it. But has he? Where does this confidence come from?

Parts 2, 3 and 4 of this series will cover each of these in turn. For now, give yourself permission to watch or read the novel ‘for academic purposes’ (i.e. guilt-free), and let us know in the comments what you think the solutions might be, and if you can find similar cases elsewhere.

Footnotes

[1] S. Rennick, Harry Potter and the Time Travel Paradox, Cogito, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2009, pp. 38-52.

[2] Robert A. Heinlein, – All You Zombies – , first published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1959.

[3] The plot summary that follows is largely borrowed from the aforementioned Cogito paper.

References

-

Heinlein, Robert A., – All You Zombies – , first published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1959.

-

Rennick, S., Harry Potter and the Time Travel Paradox, Cogito, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2009: 38-52.

-

Rowling, J. K., Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, London: Bloomsbury, 1999.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in the philosophy of time travel, the best place to start is always David Lewis, The Paradoxes of Time Travel, American Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 2, 1976: 145-152.

A Time Travel Website is a great blog focussing specifically on the philosophy of time travel, and well worth a visit.

And for a vast array of timey-wimey tropes, see http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/TimeTravelTropes.

1 comment

I dont have a solution.

Only more questions.

1. Hermione saves Harry from Remus’ attack by distracting him and creates another problem.

2. Would Harry have used the 3 hour ago memory of his uncle inviting him to live away from the Dursley clan as his “happy memory” in order to produce the patronas at that strength?