…and, more recently, financial advisors.

There are lots of interesting features of Stoicism – and indeed, the other ancient philosophical schools (we are the Epicurean Cure after all) – but I want to focus on one idea in particular and one neat (and seemingly overlooked) representation of it in popular media. First, a caveat: this piece is both brief and rather rough-and-ready, so see the further reading below for more precision and to dive deeper.

In 2001, K-Pax was released: a film about a psychiatric hospital with a patient who claimed to be an alien from the eponymous planet of K-Pax. I’m loathe to recommend a film starring Kevin Spacey, but thankfully the whole script is available online, so if you’re interested you can read it there and mentally substitute whatever person you like into the lead role.

At the very end of the film, there’s a voiceover from the main character – the possible alien – with advice for his psychiatrist.[3] First he tells us that the K-Paxians know something that humans don’t:

The Universe will expand, then collapse back on itself – then expand again. It will repeat this process again and again, forever.

At first this just sounds like a Big Bang/Big Crunch sort of picture, but in the context of what comes next, the Stoic influence becomes obvious.

Stoic doctrine speaks of a

cosmic ‘fire’ which combined the creative functions of light and warmth – this latter including that of the warm ‘breath’ or pneuma (which in its Latinized form became our word ‘spirit’) that served as the vitalizing force of the Stoic world. God is sometimes defined as a ‘creative fire that proceeds methodically to the world’s coming to be’.

Brunschwig & Sedley, p. 170

This ‘coming to be’ isn’t a singular occurrence. For the Stoics, the world comes into being and then ends again in cycles. The end is a state of total fieriness or godliness called ekpyrosis (often translated as ‘conflagration’), during which the deity sets up the new cycle.

Now there’s nothing there to worry about, just yet. It’s quite nice to think that if things don’t shake out as well as they could this time round that we (or others like us) would get another shot next cycle. But as the voiceover from K-Pax tells us, that’s not what we should expect:

What you don’t know is that when the Universe expands again, everything will be as it was before. Whatever mistakes you make this time around, you will live through again. Over and over, forever.

The Stoics thought so too:

The deity, being supremely wise, has no reason to do things differently from one world to the next. So successive worlds are indistinguishable from each other, even in their details.

B&S, p. 171.

I’ve written this sentence infinitely many times in previous cycles, and will write it again infinitely more times in subsequent cycles.

So, you might ask, why bother? Why study for an exam, if whether I pass or fail is predetermined (and not just now, but for infinitely many repetitions?) Why go to the doctor when I’m sick – I’ll either get better or I won’t. This is the charge of fatalism, and the critics of Stoics raised the same objections, sometimes called ‘The Lazy Argument’ or ‘The Idle Argument’.

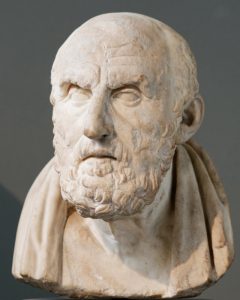

Undeterred, the Stoic Chrysippus replied that outcomes are not fated no matter what, but rather ‘co-fated’ along with other factors, such as our decisions, actions, and dispositions. That you are you – rather than someone else, with a shorter temper, a tendency to make decisions by rolling dice, or a preference for honeycomb ice-cream – factors in to how the world is. Fate gives us a push, says Chrysippus, but it works through us; how fate unrolls depends on the kinds of beings we are. (Editor’s note: I’m paraphrasing here, and Chrysippus spoke Ancient Greek.[4])

We might understand it like this: it is determined by the deity that I am who I am. But if I had been different, things would have turned out differently.

There is nothing new under a sun which, even itself, is not new.

One of the reasons people might be worried by the idea of fate is that they think it’s only appropriate to blame or praise someone for their actions – to hold them accountable – if the action originated with them.[5] For the Stoics, it’s appropriate to praise and blame people even though the world is determined, because the kinds of people we are makes a difference to how the world turns out. Fate ultimately causes the kinds of people we are, and what happens to us: “how we respond, however predictable in the light of our own past history and present character, is ‘in our power’: the responsibility for it is our own.”[6]

Scholars have different views on the nuances of Stoic determinism and what we should take from it. For instance,

In embracing this strange conceit, the Stoics may well have been attracted by its moral implications: don’t dream of what you could do, or might have been able to do, ‘in another life’, because another life would be just the same as this one. There is nothing new under a sun which, even itself, is not new.

B&S, p. 171.

But the message from K-Pax is slightly more upbeat:

[M]y advice to you is to get it right this time around. Because… this time… is all you have.

I might have typed this sentence infinitely times before, but to me, in my chair, it feels like the first time, and it always will. Fingers crossed I’ve avoided any typos.

Footnotes

[1] Not to be confused by Zeno of Elea (he of many puzzles – the Stoics were, to my knowledge, fine with the idea that Achilles could catch up with a tortoise).

[2] As Susanne Bobzien writes, “Stoic philosophy, although uniform in its core tenets, has always contained…differences in the explanations of details even among the most orthodox members of the school, and a focus on different areas of philosophy by different Stoics” (p. 2).

[3] The following quotations are taken from the script linked above, on p. 172. For accessibility purposes, you can also watch the relevant scene here: https://youtu.be/bHhtl82GsCo?t=120.

[4] And, according to one report (from Diogenes Laertius), he died laughing at his own joke. What a guy.

[5] We might also say ‘if they acted freely’, but what we should mean by ‘freely’ is a whole other philosophical can of worms. Another thing that matters for praise and blame is us being the same people from one day to the next – see this article for more on this.

[6] B&S, p. 172.

References

- Bobzien, S. Determinism and freedom in Stoic philosophy, (Oxford: OUP, 1998).

- Brunschwig & Sedley, Hellenistic Philosophy in Sedley (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Philosophy, (Cambridge: CUP, 2003), pp. 151-183.

Further Reading

You can find out more about Chrysippus in Book VII Chapter 7 of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives of Eminent Philosophers.

If you want to read some Stoic philosophy straight from the Ancient Stoics, you could start with Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations and Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic.

For a general overview of philosophy in the period there are a lot of options, but one that easily fits in the handbag is Terence Irwin’s Classical Thought (Oxford and New York: OUP, 1989).

]]>