The grandfather paradox has been discussed in countless places. but usually proceeds as follows:

If I could travel back in time, I could kill my grandfather before my father was conceived, thereby preventing my own existence. But if I was not born, how could I travel back in time to kill my grandfather?

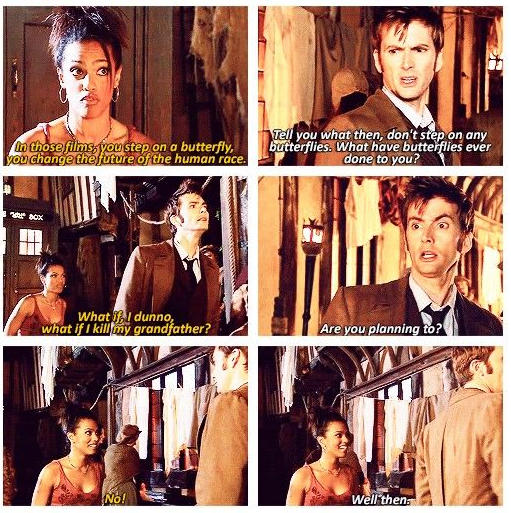

Here are just a couple of examples. First, from Doctor Who:

In the Futurama episode Roswell That Ends Well, Farnsworth warns Fry not to interact with the latter’s grandfather, lest he kill him and prevent his existence (but that’s not quite what happens...).

A common variant of this paradox is the ‘auto-infanticide paradox’, except instead of killing my grandfather, I try to kill my younger self. (Of course, our time traveller doesn’t have to be murderous to erase their existence: take Marty McFly in Back to the Future. All the time travellers who try to kill Hitler – a trope for another day – may, if they really could change the world, bring about a future they were no longer a part of. And so on.)

In all of these cases, it is argued, a contradiction ensues: I both could and could not kill my grandfather (or my earlier self). I could, because it’s tragically easy to kill people; provided I had the time machine, knowledge of where my grandfather was, sufficient training, a weapon, and so forth, I could carry out the murder. But I couldn’t, given that my existence – and thus my being there to perform the killing attempt – depends on my grandfather’s surviving to produce my father (or my younger self growing up to be me). This apparent contradiction has regularly (and I mean regularly) been employed as ‘evidence’ for the impossibility of time travel. As Lewis so pithily puts it,

If a time traveller visiting the past both could and couldn’t do something that would change it, then there could not possibly be such a time traveller.[1]

But Harry seems to be such a time traveller.

(“What?!”, you exclaim. “I don’t remember Harry trying to kill his grandfather! He briefly tried to kill his godfather, but that was a mistake, and…”

“Sshh”, I say, calmly, and then make you a cup of tea.)

Harry doesn’t kill his grandfather, it’s true. Instead, he saves a life. The ‘first’ time around – or from Harry’s perspective, prior to his travelling in time – Buckbeak seems to have been killed by the executioner Macnair. Harry hears the swish and thud of the axe, and Hagrid’s sobs. But the ‘second’ time around, with the time turner on their side, Buckbeak is saved. If that’s true, then at the very same moment in time Buckbeak is both killed and not killed. Schrödinger aside, that can’t be right.

In the philosophical literature, attempts like these to change the past and thereby generate a contradiction are called bilking attempts.[2] In order to avoid contradictions, either time travel must not occur, or bilking attempts must fail. Contradictions – especially the kind that allow people to be both existing and not existing at the very same time – are bad. Not ‘aaargh the universe will explode bad!’, despite what some fiction would tell you. Instead they’re impossible, and so if time travel led to contradictions, time travel would be impossible. And that would be a tragedy.

So, Harry’s bilking attempt (i.e. his attempt to save Buckbeak) must fail, if it’s a genuine bilking attempt…

So we know that he must fail, given the logic. But why does he fail? In other words, how do we explain his failure? What causes it? (And likewise, what causes me to fail every time I try to kill my baby self? What saves Hitler from the onslaught of time travellers?)

The short answer is that Harry doesn’t fail. It’s not a genuine bilking attempt. Harry might think he’s changing the past, but given all the other clues from the film (which is more explicit than the novel) – Hermione’s howls, the rock thrown through the window – the most charitable interpretation is that Buckbeak was never killed. The axe hit the pumpkin all along, and Hagrid’s tears were always joyous. This is the only possible version of the event that avoids contradictions and keeps the timeline consistent. Harry is filling a role he always played; he hasn’t changed the past, just precipitated the future he remembers.

But you mightn’t find that very satisfying. Generally, it’s easier to answer this in fiction than in life. It’s all very well in a story to wave a magic wand (literally, in Harry’s case), but what about if you had a time machine right now and tried to change the past? What would stop you? Do we need to posit some temporal guardian or unlikely consequences to prevent the impossible from occurring? And is it really logically impossible to change the past – would it always result in a contradiction? Are there theories of time which allow it? And if you can’t change it, how does that affect your free will?

These are all sensible questions. Well done, you. We’ll tackle them (cough, cough) in time.

If you have any time travel texts you’d like me to talk about in future instalments, or burning questions/comments, do let me know below.

Footnotes

[1]David Lewis, The Paradoxes of Time Travel, p. 149

[2]Why 'bilking'? The term (used this way) seems to come from Max Black's Why cannot an effect precede its cause? (1956).

References

- Max Black, Why cannot an effect precede its cause? Analysis, Vol. 16 No. 3, 1956: 49-58.

- David Lewis, The Paradoxes of Time Travel, American Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 2, 1976: 145-152.